In 1944, the second largest consumer co-operative in the United States was booming.

In today’s dollars, the co-op was doing almost US$12m a year in sales. Its busy staff of over 200 people was working in numerous departments. To keep it fully stocked, this co-op was getting regular full-truck deliveries from the warehouse of Associated Cooperatives in Oakland, California.

The community was so unique that the government asked iconic Works Project Administration (WPA) photographer Dorothea Lange to document the activities of the 11,000 people who lived there. Lange’s photos, however, were considered too sensitive to be seen by the public and were subsequently confiscated by the US military and withheld from public view until 1946. It was another 60 years before those photos were shown in major exhibits across the USA.

Why the delay and shielding from public view? Because the second largest consumer co-operative in America in 1944 was purposefully hidden away in the high desert of inland California. The co-op served some of the over 120,000 interned Japanese-Americans who had been unconstitutionally removed from their homes. Later, the people that lived there renamed the place either the Manzanar Internment Camp or the Manzanar Concentration Camp. It was one of ten such camps built in the United States during World War II.

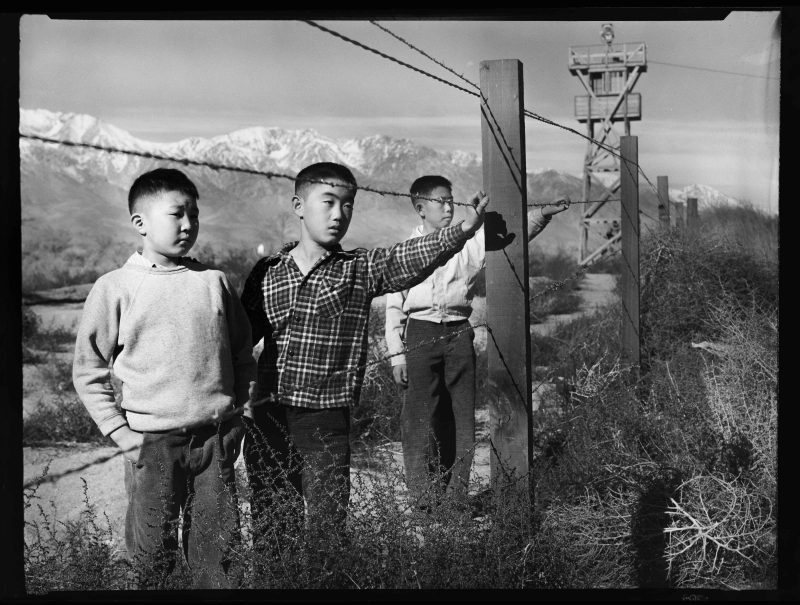

Manzanar was hurriedly built on a desolate site in a remote corner of the arid high desert in California in 1942. At nearly 4,000 feet in altitude, summer temperatures reached 110F (43C) and winters were below freezing. The 11,000 internees were Japanese American families who were rapidly and forcibly removed from their homes, farms and businesses soon after Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

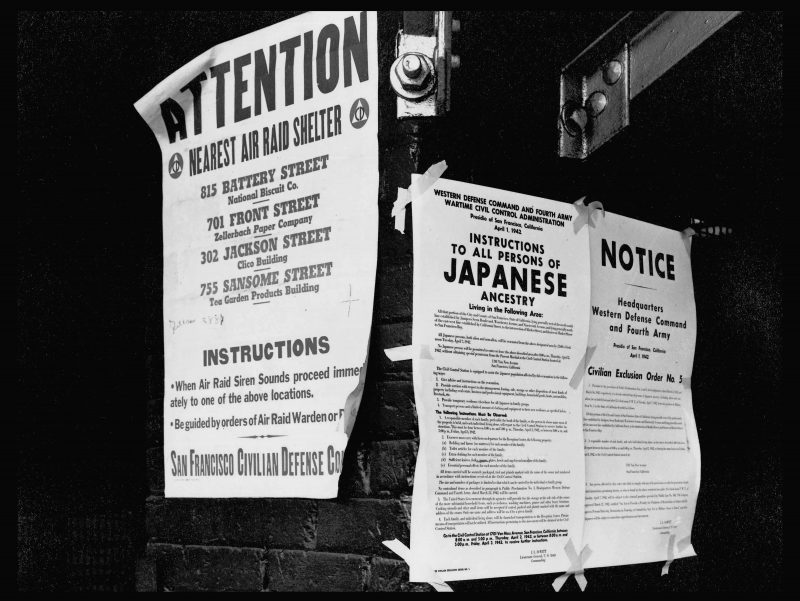

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order #9066 authorising the Secretary of War to remove anyone from the Pacific coast areas who might threaten the war effort. The internees were surrounded by barbed wire, armed sentries and eight guard towers. The shame of forced government removal and internment was finally acknowledged in 1992, and Manzanar was declared a national historic site that same year.

Co-operative enterprises with stores were set up in nine out of the ten internment camps. Those nine consumer co-operatives served over 110,000 of the over 120,000 internees. In 1944, the camp co-ops had aggregate sales of over $130 million in today’s dollars.

Five of the internment camp co-ops were weekly purchasing members of the Oakland based Associated Co-operatives: (Manzanar (CA), Minidoka (ID), Poston (AZ), Topaz (UT), and Tule Lake (CA)). Associated Co-operatives was very aligned with the internees, staffed by many conscientious objectors (COs) and led by US co-operators who were followers of Toyohiko Kagawa, the American educated Japanese Christian leader who espoused co-operatives as the “people’s economy” of Japan and the USA.

The idea for the co-ops is attributed to several components. In the setting up of the camps, it was believed that the internees would resent patronising a government-run store. Eleanor Roosevelt and other ‘New Deal’ voices felt that a consumer co-operative operated by and for the internees would be an opportunity for independence from the federal government and a mark of their own self-governance. The co-op would be the largest employer in the camp and create wage income for the internees and valuable savings for the members.

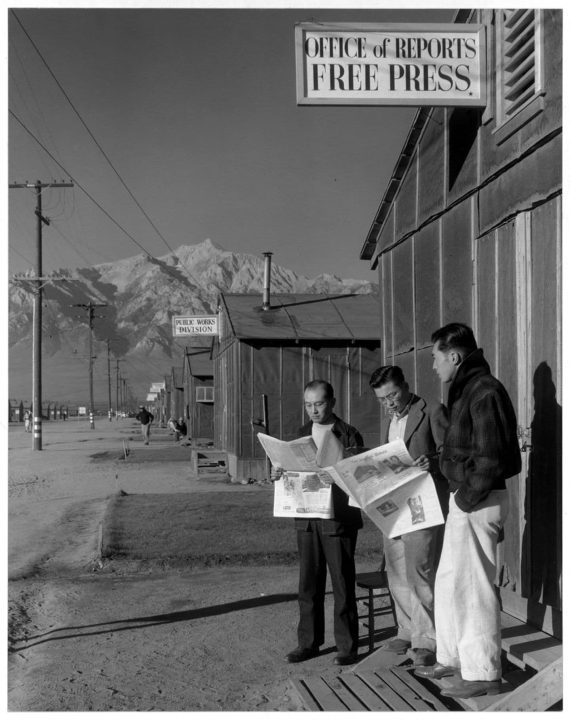

To show how the co-ops operated in each camp, let us use the example of Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises, Inc (MCE). At its height, MCE employed 239 staff, rented seven barracks and operated retail stores for food, clothing and dry goods, a canteen, warehouse, laundry, barber shop, beauty salon, shoe repair, as well as subsidizing the Manzanar Free Press – the camp’s newspaper.

Almost every adult (7,000) over 16 at Manzanar joined the co-op. It was an economic success and as a co-operative shared all the profits with the members in the form of a yearly patronage rebate. In its three years of operation, MCE paid out $150,000 in rebates which would be worth over $2m in 2019 dollars. Not bad for a remote little co-op store hundreds of miles from anywhere in California’s high desert.

World War II ended in 1945, the same year that the last of the internees were released. But there was still a great deal of hostility in California, Oregon and Washington State against the newly released Japanese Americans. As a result, many of the former Japanese American internees did not want to return to the communities where they had lived their lives but had now lost their homes, businesses, farms and jobs.

In a demonstration of principle 6 (co-operation among co-operatives), co-ops in the San Francisco Bay Area went out of their way to offer employment in leadership roles to those Californians in the internment camps who had worked for their camp’s co-op. The following internees became a major part of the executive leadership of the Bay Area consumer co-operatives: Min Takamoto became the general manager of the Palo Alto Coop; George Yasukochi, the controller of the Berkeley Co-op; Robert Sataki, the administrative assistant and Hachiro Yuasa, the Berkeley Co-op architect; E. J. Kashiwase, the head of accounting, Associated Coops; and John Kitamata, the produce buyer.

There was one final unique link in this circle of humanity. The Japanese Americans from the camps returned to help build a vibrant co-op post war economy in the Bay Area. Over in Japan, Kagawa, as head of the Japanese Consumer Co-operative Union, asked the Bay Area cooperatives to support a programme that would teach young Japanese co-op managers to kick start co-operative retailing in a starving post-war Japan.

Through what they learned at the Palo Alto and Berkeley Co-ops, these young leaders went back to Japan with modern American practices to revitalise their war-ravaged movement. The Japanese American Bay Area co-op employees took on the role of language, cultural and professional intermediaries. This inter-coop linkage continued annually for decades until the Bay Area co-ops closed in the late 1980s. Nevertheless, there is an amazing legacy of that post-war friendship. Those food consumer co-ops in Japan now serve 22 million Japanese families. Combined, they have a 3% market share of all retail food in Japan, making co-ops the fourth-largest retail chain in Japan.

Regrettably, the stain of the relocation and internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans has left an indelible mark on the country’s heritage. On the other hand, the Japanese cooperative motto – “Peace and Better Life” – can be equally applied to the internees in the camps, the building of co-operatives in the camps, the growing of the Bay Area co-operatives and the rebirth of the Japanese consumer co-op movement. Together, they are enjoined as one continuing effort to build a world without war – and a better and more just society here on Earth.

David J. Thompson is a board member of the still existing Associated Cooperatives, as well as a prolific writer about cooperatives. He has authored and co-authored a number of books and written over 400 articles about cooperatives. He is writing a book entitled, “The Spirit of Cooperation: Utopian Colonies, Concentration Camps and Cooperatives in the Lives of Japanese Americans.” If you have a memory or story about the co-ops in the camps, please get in touch with David at [email protected]. See www.community.coop.