South Sudan is troubled. Despite it gaining independence from Sudan last July, the two nations are still at odds, especially over control of the oil produced along their border.

Corruption in South Sudan is rife. In June, a letter from President Salva Kir, asking 75 ministers and officials to return $4 billion of stolen government money, was leaked to the press.

Infrastructure is far from adequate – the country’s first major tarmac road was built this year. And poverty is the norm; pre-independence, the United Nations Development Project put South Sudan’s poverty rate at 50.6 per cent.

Nevertheless, there is hope that co-operative agriculture and finance, coupled with the benefits of economic and infrastructural growth, could make rural South Sudan a garden for the region and beyond. It is an optimistic vision, but this young nation has yet to fail.

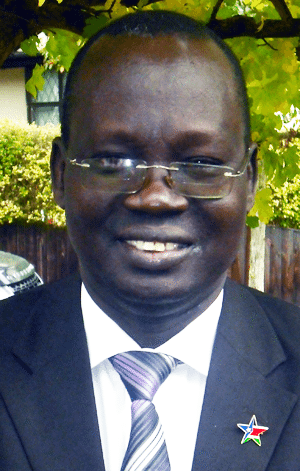

Michael Tongun Martin, South Sudan’s minister for co-operatives and rural development, says his country could rival Kenya as an exporter of food, and it could do it co-operatively.

“We have the fifth largest area of arable land in the world,” he says. “We have rainfall for seven months of the year.

“Half the course of the White Nile flows through South Sudan. People imagine it’s a desert country. That’s very far from the truth.

“Given that we’re just a new country we want to produce not only enough food for ourselves, but also enough to become a major exporter of food.”

Mr Martin points to economic success stories like the Kenyan fair trade flower industry and its hugely successful fruit and vegetable export sector as his inspiration.

He admits Kenya had a relatively well-developed infrastructure and a more stable political landscape. But, he says, given time, South Sudan has the potential to do the same.

An economic zone is already in development, thanks largely to investment by South Sudan’s main economic partner, China. This trading space will, Mr Martin says, open the country to foreign partners and increase the country’s GDP.

There are even plans for South Sudan and its neighbours to build a shipping canal linking the east and west coasts of the continent. The move, if successful, would reduce the cost of moving a container ship between the Indian and Atlantic oceans by about $10,000 and transform the fate of Central Africa.

South Sudan’s friends in the region, including Ethiopia, Uganda and Kenya, are not only potential customers, but co-operative partners. Each has a strong co-operative economy and a well established co-operative movement.

In Kenya, for example, the Ministry of Co-operative Development and Marketing estimates there are eight million members in 13,000 registered co-operative societies nationally. A member of the Kenyan movement has been seconded to South Sudan to support its co-operative sector.

Mr Martin, who studied international development in the Philippines, estimates there are currently only one hundred or so agricultural and consumer co-operatives in South Sudan. His remit is to help small producers develop into co-operatives and support them with marketing, management, packaging, storage and mechanisation.

“We also want them to take care of the environment, plant more trees and make sure we don’t contribute to climate change,” he says. “We know climate change is real.”

Agricultural production levels are currently low, but the government is providing tractors and other inputs to improve capacity.

Mr Martin admits it is not enough. “Technology allows us to access irrigation from the Nile 300km away,” he says. “Financial capacity is the issue.”

His ministry’s priority is to set up co-operative bank. It also plans to introduce saving and credit co-operatives alongside rural agricultural and consumer co-operatives.

“We need to make sure farmers don’t have problems getting credit and insurance. If we achieve this, production levels should improve.”

Unfortunately, he says, continued instability in the north is hampering progress. “Because of the crisis this has still not been accomplished,” says Mr Martin. “We’re looking forward to finalising this issue by referendum next year, perhaps in October.”

A comprehensive peace agreement, drawn up by the United Nations, says the people of the border areas must decide themselves whether they want to be part of Sudan or South Sudan.

In many ways this is a familiar African tale. The natural resources exist, but the financial capacity, infrastructure and political stability to see strategic development through do not.

Amid growing competition for resources and markets from large international businesses, South Sudan is looking for ways to empower its citizens. Like many African nations, it has put co-operatives and fair trade at the heart of its rural development strategy.

The logic is clear. Co-operation with fellow farmers, neighbouring countries and the international co-operative movement will help smallholders, farmers and workers improve their negotiating position along the value chain.

“We believe co-operatives will help change the livelihoods of the people and help them have income and improved life conditions,” says Mr Martin. “We’re very optimistic, the potential is plenty.

“The co-operative model will make income distribution fair, it will eliminate inequalities. It will provide opportunities for everyone to participate and gain income. It’s an opportunity for us to reduce poverty.

“Our country is open to investment by all,” he says. But he adds that farmers must organise into co-operatives if they are to be able to negotiate in the new South Sudan.

“The United Nations, The World Bank, the World Trade Organisation and all the African governments support co-operatives,” he says. “In this co-operative year, I’ve been very impressed with the co-operative movement’s concern for the dignity of humanity. Now we’re beginning the decade of the co-operative.

“If we can persuade aid agencies, multinationals and governments around the world to bring in co-operative values then the future is bright. But if it’s left to interest groups in government we’re in trouble.”