Adolf Hitler’s hatred and intolerance of sections of society is well documented, but less known is the Third Reich’s complicated and ultimately equally destructive relationships with co-ops, both in Germany and across wider Europe.

The co-op movement in Germany developed around the same time as consumer co-operation in Britain and producer co-operation in France, but with a focus on thrift and credit societies, the legacy of which can be seen in the country’s Volksbanken and Raiffeisenbanken today. Germany also held the first examples of housing co-operative movements independent of retail co-operative societies, which were established by Bismarck’s government in order to improve living conditions of workers and help prevent revolution.

In the early 20th century, the majority of the German consumers’ societies were affiliated to the Central Union of German Consumers’ Societies (Zentralverband deutsche Konsumervereine), the national organisation for consultation, propaganda, and defence, which was established in 1903.

Gillian Lonergan, head of heritage resources at the Co-operative Heritage Trust and National Co-operative Archive, says: “In 1939, the Co-operative Union (now Co-operatives UK) published a 24 page pamphlet called Co-operation Under the Nazis which was ‘compiled by the staff of the International Co-operative Alliance, who have had special opportunities for securing accurate and authentic facts’ – though as it was published in 1939, it is not possible to guarantee that it was completely impartial.

“The pamphlet talks about the problems of the German co-operative movement from 1933 onwards – it says that in 1932 there were 949 societies in the Central Union with 10,987 shops, 48,095 employees and 2.8 million members.”

It describes how The National Socialist Party, while still in opposition, did everything in its power to hinder the development of the consumers’ co-operative movement: “Throughout the country the societies and their leaders were vehemently attacked, and the Party press and Nazis everywhere fomented, and profited by, the private traders’ natural hostility to their co-operative competitors,” reads the pamphlet.

Ms Lonergan adds: “It goes on to talk about breaking of shop windows, the seizure of co-operative shops and their closure or picketing by stormtroopers. A number of co-operators and co-operative officials were arrested.”

However, the pamphlet also notes that, significantly, traders’, artisans’ and agricultural co-ops, (“ie those formed by the middle classes”), were not attacked, as the Nazi party drew its most active members from this section of the population. “They looked upon consumer co-ops as a movement to eliminate the small trader and artisan in order to pave the way for Marxist Socialism.”

In the spring of 1933 the situation for consumers’ co-operatives had became so bad that the co-operative leaders in Hamburg, in agreement with the Zentralverband in Cologne, approached the Reich government to request protection for co-operatives and the correction of misleading statements in the national press.

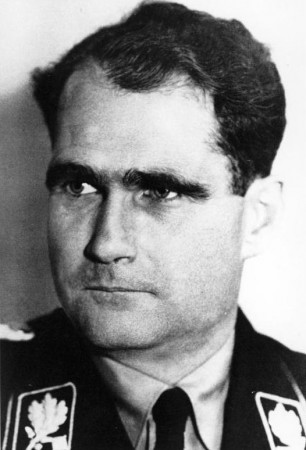

The pamphlet adds: “On 9 July, Rudolph Hess, Hitler’s deputy, made an official declaration that no one was to be attacked because of his membership of a co-op society, and that strife between different economic groups must cease.”

A law on consumers’ co-operative societies passed on 21 May 1935 had three “main objects”: To restrict the development of the consumers’ co-operative movement; to liquidate the funds of the consumers’ movement; and to create the legal conditions for a complete transformation of the business methods of the consumers’ societies, including the deprivation of their co-operative character.

But even until the late 1930s, there appeared a semblance of respect from German National Socialists towards the integrity of the co-operatives, “probably because of the need for appealing to organised workers,” says Florence E. Parker and Helen I. Cowan in their 1944 book Cooperative Associations in Europe and Their Possibilities for Post-war Reconstruction. However, the country’s Consumers’ Cooperative Congress held in November 1938 revealed a changed attitude. “Beginning with July, Nazi-inspired notices issued by the Zentralverband had required that all Jewish members and firms be excluded from the Union because ‘the German co-operative will and the Jewish trading spirit’ were contradictory.”

They add: “More than one third of all the delegates at the Congress were uniformed Nazis; many trusted cooperative leaders failed to attend because of racial exclusion, suicide, or, as the obituary notice in the Zentralverband report explained, because they ‘have departed from us since the last Congress’.”

It was made clear to Congress that the National Socialists expected the co-operative societies to play their part in the new Four-Year Plan.

In March 1938, the whole network of consumers’ co-operative organisations in German-occupied Austria – some 220 associations and 300,000 households – had been put under the control of a commissioner appointed by the Nazi leaders. In the winter of 1938, the secretary of the “adjusted” Austrian associations established a new board in Germany “to examine each co-operative society individually and submit proposals for fusions, separations, or possibly the liquidation of the movement.”

On 18 February 1941, a German decree announced plans for the liquidation of the Austrian (and German) consumers’ co-operatives.

Individual co-operators were targeted by Hitler too, with several individuals in the UK featuring in the Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. (Special Search List Great Britain), which became known as The Black Book. The list was an appendix to the Informationsheft G.B., the Gestapo handbook for the invasion of Britain, which contained the names of 2,820 prominent British residents to be arrested upon the successful invasion of Britain by Nazi Germany.

Those targeted in the list, which was released last month, encompassed authors, activists, politicians, socialists and socialites, including Sylvia Pankhurst (daughter of Emmeline), Virginia and Leonard Woolf, H. G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, Sigmund Freud, Willie Gallacher, Robert Baden-Powell – and five people with strong links to the co-operative movement.

Scottish politician George Nicoll Barnes, who was Labour Leader from 1910-11, was a fervent supporter of the International Labour Organization and served as chairman of the Co-operative Printing Society, while Theodor Cassau was an economist specialising in statistics, trade union policy and the consumers’ co-operative movement. Albert Victor Alexander, a British Labour Co-operative politician, was three times First Lord of the Admiralty, including during the Second World War, and then minister of defence under Clement Attlee. And Samuel Perry, later a Member of Parliament, was the first national secretary of the Co-operative Party (and the father of tennis player Fred Perry).

Also on the list was Robert Palmer, a Labour Co-operative member of the House of Lords. He had become a director of the Manchester and Salford Co-operative Society by the age of 21, then after serving in Egypt, Belgium and France during the First World War, was appointed cashier and financial adviser of the Co-operative Union, before becoming the organisation’s general secretary. He also served as acting president of the International Co-operative Alliance from 1940-46 (when president Väinö Tanner of Finland was unable to carry out his duties because of the war), before being elected in his own right until 1948.

Similar lists were drawn up – and used – for the USSR, France, Poland and more. The only place in the British Isles that experienced these roundups was the Channel Islands.

The one monument to co-operation that Hitler did hold attachment to was Rochdale Town Hall, built in the Victorian Gothic Revival style at a cost of £160,000, following a suggestion from the newly formed Rochdale Corporation. It opened in 1871, with the Rochdale Pioneers in attendance, in the town than birthed the movement.

It has been suggested that the building, and its stained glass, came to Hitler’s attention while he was staying with his half-brother Alois Hitler, Jr. in Liverpool in 1912-13 – or through military intelligence or information from Oldham-based Nazi sympathiser William Joyce. But however he came about the information, it is said that Hitler admired the architecture so much that he planned to ship the building to Nazi Germany had German-occupied Europe encompassed the United Kingdom. Rochdale was broadly avoided by German bombers during the Second World War.