When they set up their co-op in 1844, the Rochdale Pioneers developed seven principles that are still followed around the world today.

And those values, which show how co-ops are different from other forms of business, are more important than ever. A recent YouGov survey for Co-operatives UK found just 36% of Britons believe most companies in the UK are fair to consumers, down from 44% in 2000 and 61% in 1983. But 62% trust businesses such as the Co-op Group or John Lewis, which are owned by their members, who have a say in how their organisations are run.

But are the old co-op values losing ground in the movement?

Ethics gaining ground

Traditionally, co-ops are based on the values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity and solidarity. The ICA statement on co-op identity points out that members should also believe in honesty, openness, social responsibility and caring for others.

The Rochdale Pioneers’ society evolved into today’s Co-op Group. While being member-owned and governed remains crucial, the business places strong emphasis on concern for community. A current campaign focuses on tackling modern slavery across its supply chains.

“In the 1860s, when the Rochdale Pioneers took a strong line against slavery by boycotting cotton produced in the southern states during the American Civil War, they were upholding the same values,” says Sterling Smith, a former official of the International Labour Organization.

“Co-ops need to look at co-operative values and principles and see how they can be put in practice today and not have the same corporate social responsibility strategies as plcs.”

Ethical trading and serving communities are a consideration for other big co-ops too, following the rise of the conscious consumer.

The recent Global Retail Trends report by accounting firm KPMG revealed that honesty and authenticity were the attributes that mattered most to customers. Businesses need to stand for something and reflect that message consistently throughout the business, from top to bottom.

According to Deloitte’s Human Capital Trends 2018 survey, businesses are no longer judged just on financial performance and the quality of products and services, but also their social impact. The survey involved 11,000 business and HR leaders across 124 countries. Around 77% of respondents said that citizenship, defined as an organisation’s impact on society, was important, with 18% saying it was a top priority.

Related: A new overview of the history of co-operation

Other trends include increased transparency, higher expectations from millennials over corporate social responsibility, and a growing number of businesses taking a political stance.

Should co-ops seek to position themselves as leaders in these areas? A 2006 research paper by Sonja Novkovic pointed to literature which questioned social responsibility as a co-op “trademark”, given that many investor-owned businesses were introducing corporate social responsibility and business ethics.

She surveyed 60 co-op managers and board members from Canada and the USA. Around 5% found the co-op business inferior to investor-owned models – and 23% of respondents, mostly from large co-ops, saw profit as the key goal.

Overall, 93% of respondents found co-op values and principles important for the functioning of their co-operative. Respondents from consumer, agricultural, housing and utility co-ops chose democracy as the most important co-operative value. Managers and representatives from financial co-operatives and credit unions went for self-responsibility. Generally, equality was second most important value, followed by self-responsibility and equity. The last on the list was solidarity, even though it was listed as important by 62% of respondents.

The study revealed that while honesty and openness are more important to the managers, social responsibility and caring for others matter more to board members.

The importance of sector

In 2014, a survey by Sebastian Hill and Reiner Doluschitz of more than 300 managers of retail and banking co-ops in the German state Baden-Württemberg identified key values. The top five co-op values were: reliability and honesty (joint first); sustainability; fairness; and security. Thus, there were values in the top five, which are not mentioned by the ICA in its identity statement.

Related: How do co-ops rate against other business models?

Managers identified other factors such as “good and fair customer advice”, “proximity, partnership and professionalism”, “commitment” and “sense of community”. There was general agreement between sectors, but banking co-ops tended to place a stronger emphasis on fairness, security, reliability, honesty and sustainability, due to the lack of public trust in the banks.

The founder of the German co-op movement, Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen, based his model on solidarity and self-sufficiency – values no longer seen as crucial by all co-ops in the country.

Multinational models

For large co-ops, maintaining co-op values and principles while keeping up with business rivals is a challenge. The need to compete can also see them adopt policies that contradict those values and principles. And globalisation has pushed many co-ops to go multinational by establishing subsidiaries.

In his 2016 paper on the Mondragon Group’s Chinese subsidiaries, Anjel Errasti describes the model as “coopitalist”.

Mondragon, a Spanish federation of worker co-ops, was set up around the concept of community welfare and solidarity. It is guided by the seven traditional co-op principles, with three more added to reflect the importance of workers owning capital and the preservation of jobs.

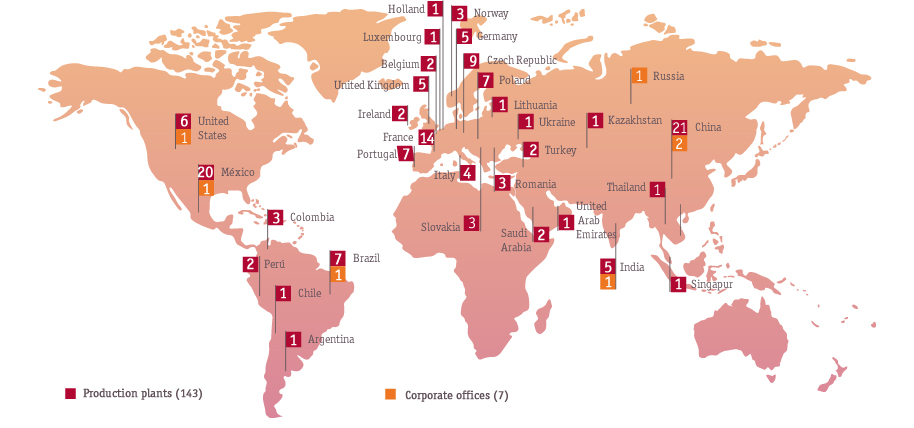

In the 1990s Spain’s industrial sector met fierce competition from foreign multinationals. In response, Mondragon created subsidiaries abroad without closing plants at home. Today, it employs 74,635 people and has a turnover of €12bn. Around 12,000 people work in its 140 foreign production subsidiaries – but none of these is a co-op. Unlike worker-members in Mondragon’s Basque Country base, workers abroad have no stake in the business, the distribution of profit, the election of governing bodies or the daily management of the firm.

The research paper found that these workers in felt disempowered. Mondragon has aimed to promote employee participation in some of these subsidiaries and has talked about converting them into co-ops – and some domestic subsidiaries have indeed been converted. But no foreign subsidiary has been transformed into a co-op, partly because there is a lack of legislation on co-operatives in some of these countries.

Errasti’s research concluded that the management of human resources in Mondragon foreign subsidiaries did not fit well with the people-centred approach of co-ops.

Lose values, lose everything?

Failure to understand and implement co-op values can lead to co-op failure. A 2016 study by Peter Couchman and Murray Fulton – When Big Co-ops Fail – indicates that co-ops which fail present similar early warning signs. These include falling silent on co-op identity and having managers with no interest or belief in the model.

The research is based on analyses of crises at big co-ops. It found that directors who fail to understand their role in a co-op are likely to appoint managers who are not supportive of the movement’s values and import mainstream solutions rather than adopt a co-op one. The paper suggests the root of failure is being unable to understand the nature of a co-operative.

“The earliest sign is a co-operative which sees being a co-operative as a problem, not a solution,” they warn.