The centenary of the end of World War I is commemorated on 11 November. One of the bloodiest conflicts in history, it resulted in more than 16 million deaths and left much of western Europe in ruins.

Here, Co-op News makes its own gesture of remembrance by looking back at some of the stories it published between 1914 and 1918, which can be found at the National Co-operative Archive.

The first notice of the war was published in Co-op News on 15 August 1914, when the paper called on co-operators to continue to trade in “the right way” by not increasing prices or creating panic.

Co-op News maintained a balanced approach throughout the war and tried to include a range of views and perspectives from service men, co-operative employees and co-operators from other countries.

On the frontline

One account of the conflict came from Private Bates of the CWS Sun Flour Mills in Trafford, who described his experience in the Battle of Mons in an article from November 1915.

He wrote: “I went five days and nights without any sleep … we did not get any ordinary food until we almost reached Paris three weeks later and lived as best we could on apples and pears”.

Employees from the flourishing co-op movement were quick to enlist.

Among them was Pte Handel Crawshaw. A former employee of the News, he quit his three-year placement to enlist at the age of 20.

He wrote on 28 November 1914 about his trip to Egypt with other soldiers and the training they did in the desert. “It is winter here but I can safely say it is as hot as the English midsummer,” he wrote.

Pte S.B. Ankers, an employee of the Co-operative Insurance Society, wrote to the News in April 1915 to thank the CWS Employees’ Relief Fund for a package he had received. He said that, as he was writing, there was a sniper near his trench, which he described as a mere “nuisance”.

Related: Co-op Group pays tribute to CWS colleagues fallen during WWI

“I am glad to tell you that we successfully advanced about 200 yards the night before last, and only suffered about four casualties in our battalion,” he wrote, referring to a battle that was part of the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign, an attempted invasion of the Ottoman Empire.

During the war, the CWS decided to pay employees who had been called up or volunteered their full wages, less government allowances and thrift fund contributions. Furthermore, on 6 November 1914, the CWS took the decision to provide an amount equal to three months wages to widows who had lost their husbands in the war, until the government legislated to support them.

By the end of the war, the society had spent £538,000 on supplementing wages. It also guaranteed employees their jobs on their return.

Co-operators at home

British co-operators who remained at home were also involved in the war effort. Co-op News reported on 13 October 1914 that members were helping to raise funds while co-op societies were sending supplies to soldiers.

According to the report, in Grantham, Lincolnshire, where 16,000 soldiers were encamped, the Grantham Co-op Society supplied them with large quantities of provisions, including 10,000 lbs of bread daily from its own bakery.

On 2 October 1914, the CWS set up a fund to assist Belgian refugees who had arrived in the country. They stayed at Chevin Hall in Otley, near Leeds, a home owned by the North West Co-operative Convalescent Homes Association.

Other convalescent homes, such as Gilsland Spa near Newcastle and homes belonging to the Southern Co-operative Convalescent Fund, were taken over by the government and used as military hospitals for the duration of the war.

Related: Sale of white poppies sets new record for Armistice centenary

In September 1914, the CWS branch in Newcastle allowed the army to use the staff dining room to provide breakfast, dinner and tea for its 600 soldiers. Canteens were set up by the CWS in other parts of the country as well.

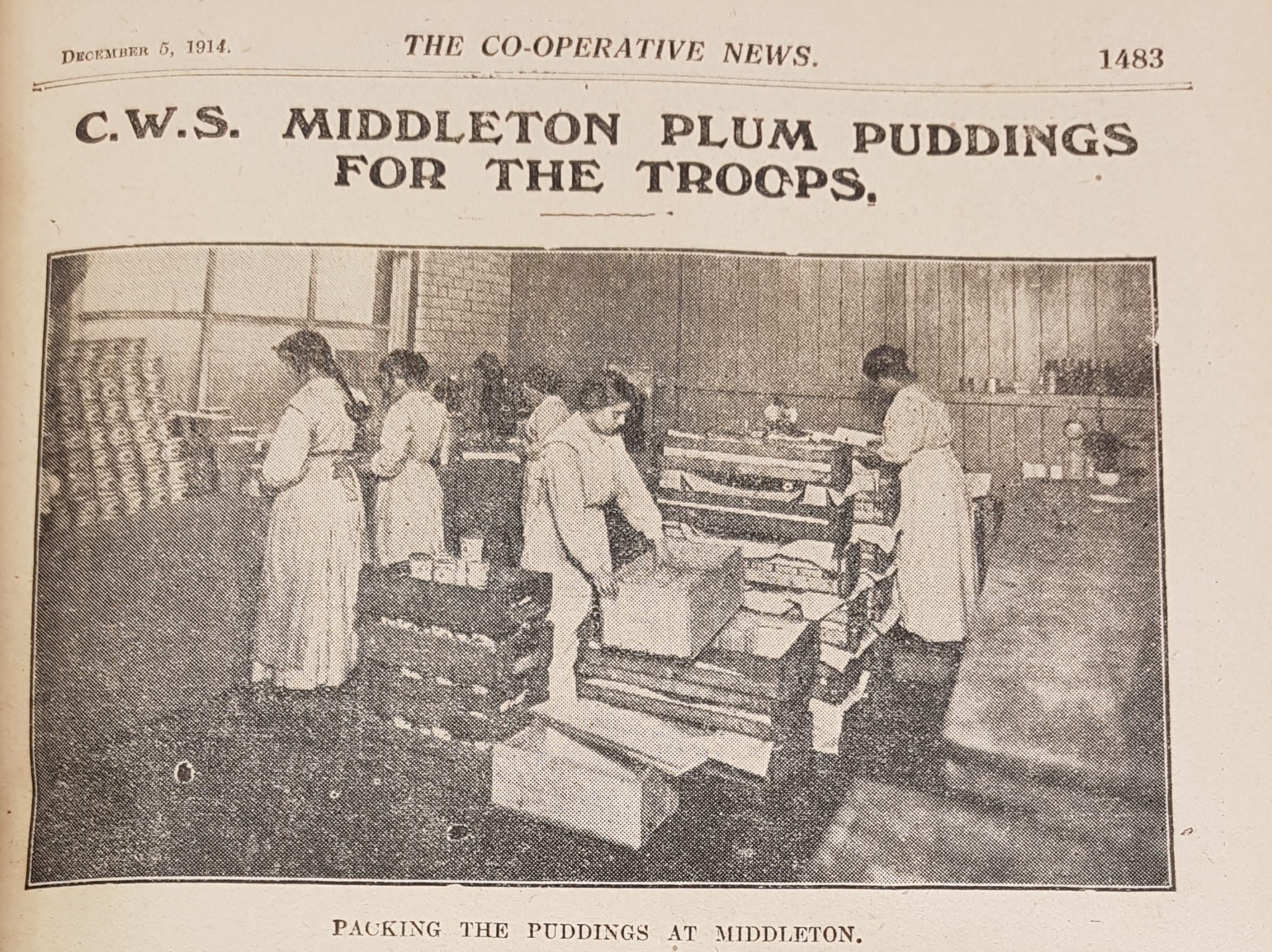

Another Co-op News story from December 1914 reports how a CWS factory in Manchester, which produced jam and confectionery, sent Christmas puddings to France for distribution, using one of its ships – the SS Fraternity – to transport the goods to Rouen, where they were distributed to soldiers.

A balanced coverage

In the initial months of the conflict, a recurring theme in Co-op News was how to prevent mass unemployment.

On 22 August 1914, Frederick Rockell wrote: “Outside the question of military or naval failure, the greatest danger to be apprehended from war is unemployment.” He called on people to spend their income in the same way they did before the war to help preserve the country’s

manufacturing industry.

A Women’s Corner article on 12 September 1914 encouraged women to support jobs by reinforcing the co-op drapery trade and finding work for women.

On 23 August 1914, a story looked at how co-ops were reacting to the panic over food demand. Co-operation among co-operatives was more important than ever, it argued. “The City of Liverpool and Toxteth Societies are keeping each other informed on the matter of prices, and there is little doubt that by their joint efforts they are making the situation less trying for the workers,” it said.

Most retailers had to up prices during the war. But, according to reports in Co-op News, co-ops tried to sell products at more affordable prices.

Columnists in the News were concerned about the fate of the International Co-operative Alliance and the impact of the war on international co-operation. “Co-operators are fighting one another,” said an article on 29 August 1914.

ICA secretary Henry May told a London conference in September 1914: “When all is past, we shall begin again and build up new”. After the war, he convened a new international congress in 1921.

Calls for a “new Europe”, in which ideas and principles of co-operation would govern the continent, were echoed in a comment piece by J. A. Flanaghan published on 19 October 1914. Arguing that millions of Europeans were co-operators who had “vowed eternal friendship” and “pledged themselves to peace”, he wrote: “Co-operation provides not only a remedy for our troubles, but a preventative.”

A December 1914 article by H.E. Oving explored the possibility of creating a post war “United States of Europe”, in which states would trade freely and people could travel across borders.

Related: White poppies tell the story of the alternative Remembrance Day

Another concern was the journey of refugees from Belgium and France. In 1914, the CWS closed its office in Rouen, France, but its employees were given the chance to come to England. Among them was Mr Marquis, who told a Co-op News reporter on 19 September 1914 how he left Rouen on 1 September and crossed the Channel on the CWS’s New Pioneer ship. He described the general feel of anxiety in France and the kindness with which English troops had been greeted in Rouen, as well as the large numbers of Belgian refugees arriving in France.

A later issue included an interview with Theophile Claes, manager of a co-op in Louvain, Belgium, who told how he spent three days in filthy cattle vans as a civil prisoner of the German troops entering the town. He told the News that German soldiers were setting fire to houses and committing “acts of vandalism”.

Co-operators were also among the first to welcome the refugees, who were described as “guests”. On 18 September 1914 the Co-operative Union issued an urgent appeal for the Belgian Distress Fund, to help refugees arriving in the UK.

“Belgian refugees to the number of many thousands are now entering this country and will have to be provided for. We feel that it is the duty of everyone to assist in this object”, read the call.

Co-op News readers were also informed about the fate of French co-operative organisations. In the early days of the war, the Paris Co-operative Federation set up a National Relief committee, running soup kitchens where meals were provided at just 20 centimes per head. Stories also described how Swiss co-operators helped to feed the country during the war, with support of the Co-operative Union and the Basel General Co-operative Society.

On 7 September 1914, the paper published a letter by Rennie Smith, former student at the Ruskin College and Co-operative Scholarship holder for 1912, providing an insight into his confinement in Germany. Mr Smith said his treatment had been “exemplary” and he had been allowed to continue his work in prison. He added that Englishmen had been put in prison in retaliation to how Germans in England had been treated.

When British ocean liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed by German U-boats in 1915, leading to civilian losses, Co-op News suggested the Kaiser was responsible and predicted that the USA would join the conflict.

The same year the News published an appeal by the ICA for a fund for “alien enemies” – those from Germany, Austria and Hungary who had lived peacefully but had their lives affected by the war.

As the conflict went on, the coverage started to touch on issues such as food shortages and conscription.

The News included articles with tips on how to increase food supplies by bottling fruits, and sowing and planting vegetables. Co-op News pages from January 1918 explored how to cope with famine, advising people that they would need to eat less, stop having sugar, tea, bacon, and eggs, take less milk and reduce bread ratios.

The treatment of co-operatives during the war intensified the movement’s efforts to obtain political representation in the House of Commons. The societies received minimal supplies while even management were often drafted. The campaign led to an Emergency Political Conference on 18 October 1917 where the Co-operative Party was formed.

Calls for a Co-operative Commonwealth

The edition of Co-op News after the armistice looked at how co-operation should be used to reconstruct the nation and create a co-operative commonwealth.

In a second issue, published on 23 November 1918, the paper included an in-depth analysis of its coverage. “All during the war period we did what we believed – and still believe was the most important duty that devolved upon a serious newspaper,” it said.

“We have had no light task during these years of war. To have shouted with the crowd would have been so much easier than to have taken an independent course […]

“We tried to give a fair and accurate, uncoloured view of the events in foreign countries.”

A tribute to those who lost their lives

Many of those killed during the four-year conflict were co-operators. It is difficult to estimate the exact number of co-operative employees and members who lost their lives in the war. In 1930, the CWS opened its new bank premises in Manchester, which included a national memorial naming 600 employees who had not made it back home. The idea for the memorial came from the Manchester Ex-Servicemen’s Association, who contributed £100 towards it. Other CWS premises had their own memorials, such as the Longton Pottery Works, the Manchester Boot Department and the London branch memorial.

With its coverage of the Great War, Co-op News not only brought the horrors of the frontline to the public’s attention, but also showed how communities were coming together to overcome challenges. While the world was at war, Co-op News wrote about a Co-operative Commonwealth and international co-operation.