Established more than a century ago, The New School was set up in New York City as a haven for academic freedom and intellectual inquiry. As a private, progressive, research university, it now has five divisions – design, liberal arts, performing arts, social research, and public engagement – and is home to the Platform Cooperativism Consortium.

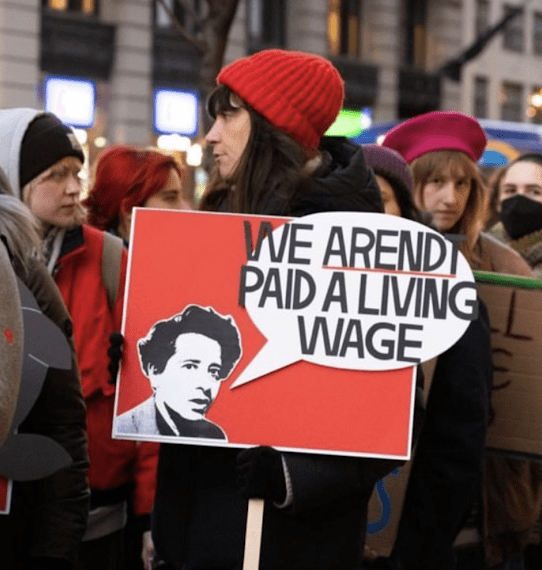

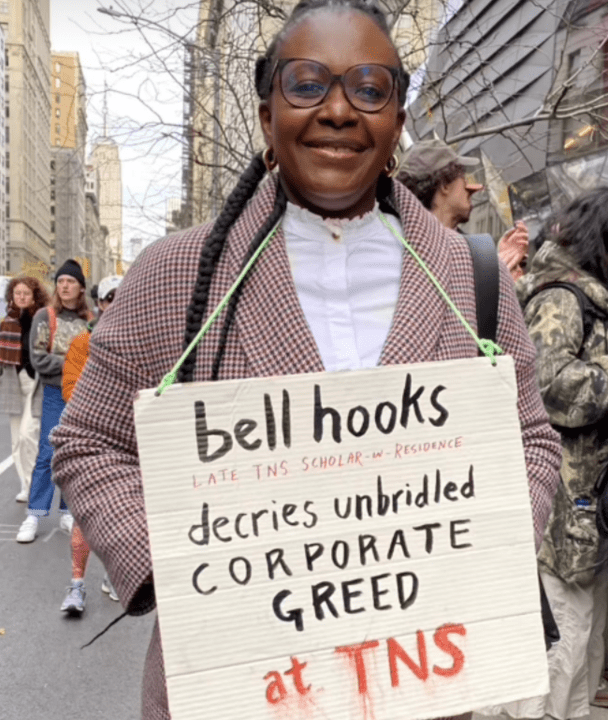

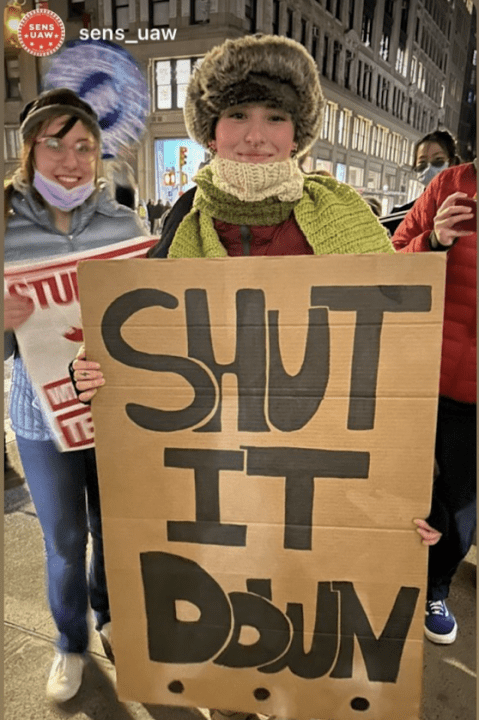

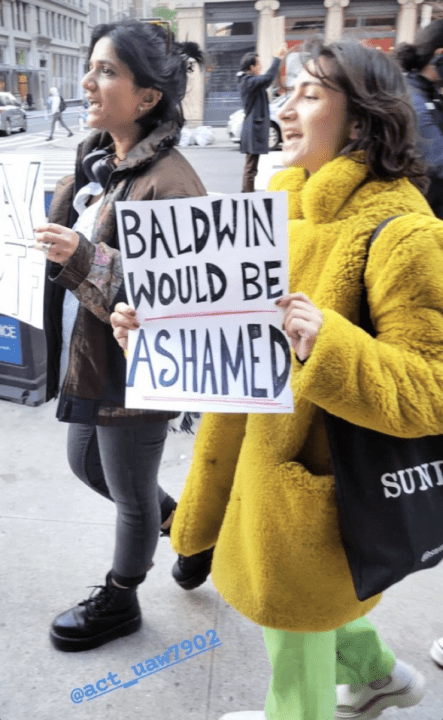

Founded on the principles of community self-governance and social justice, The New School, through a historic strike fueled by the solidarity of its faculty, students, and staff, has secured better pay and health insurance for its part-time faculty. Though the strike has ended, the echoes of its impact continue to reverberate through the halls of the university.

The New School leadership threatened to terminate pay and health insurance for all who participated in the strike. In response, students took over the university. And although the strike is over, they are demanding that the university return to its founding principles.

As the year 2012 drew to a close, I approached the president of The New School with a proposal for a co-operative college. And six years later, a former student at the university penned a thesis, with employees holding sway over all institutional policy and decision-making. This proposal was founded upon the conviction that cooperativism is a cornerstone of The New School’s history, and that the university’s capitalist model should be replaced with a co-operative model in which workers hold sway over the university’s assets and have the power to elect the board of trustees. Although I initially doubted the feasibility of converting the university into a co-op, I now believe that starting a co-operative college from scratch may be a viable option.

Related: Co-op Party report makes recommendations for the future of education

This proposal, at its core, was a response to the failure of private and state-supported universities to serve those who depend on them. In recent years, learners have faced rising tuition fees and the marketisation of higher education, leading to an average federal student loan debt balance of over $37,000 (£30,500, €34,800) in the United States. Meanwhile, adjunct instructors suffer from low pay, job insecurity, and a lack of voice in governance. The students are worried about their employment prospects after graduation, and the instructors are feeling overwhelmed by the increasing workload and uncertainty about their job stability. It is uncertain who, if anyone, benefits from this arrangement.

The critique of the neoliberal university has been thoroughly examined, yet there has been little focus on finding solutions to the identified issues. It is time to shift our focus from solely highlighting the failings of the corporate university and start exploring practical, near-term solutions that can enhance the accessibility of higher education. All those who depend on private universities like The New School will not be able to enact meaningful change without the backing of enforceable power and ownership. While employee ownership and worker co-operatives have shown promise as successful business models, there has been limited experimentation with these structures in the American higher education sector. It is uncertain whether these models would be a suitable solution to the business and democracy challenges faced by many universities.

On the other hand, it is clear that without structural power, the leadership of the university will remain subject to capitalist logic. Changing the leadership of the university without addressing the underlying power structures is akin to replacing the costumes in a “theatre of democracy”; it fails to confront the fundamental power dynamics at work.

The idea of alternative universities may seem radical, but it is not without precedent. The New School student occupations, past and present, and the do-it-yourself universities of the past, such as the Free University Movement and Hampshire College, show that there are alternative ways to approach higher education. These ideas are also being embraced by learning initiatives that utilize the potential of the internet, such as Peer to Peer University, University of the People, The Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, and the School for Poetic Computing. It should be noted, however, that the absence of accreditation for some of these programmes may be a barrier for potential students.

The prospect of a co-operative university, owned and operated by those who stand to gain or lose from its actions, is an exciting one. No longer would the decisions that shape the futures of students, faculty, and staff be made behind closed doors by a select few. Instead, the power would be placed in the hands of those who have the most at stake, giving them a vested interest in the process. Imagine a university where the needs and concerns of all stakeholders – from the security guards, students and their parents, janitors, faculty, and staff – are equally important when decisions are made. A participatory budgeting model would be one step in this direction. It would create a more equitable and inclusive institution, one that better serves all members of the university ecosystem and the communities in which it is located.

The accredited co-operative university of the future could be more than just a place for learning – it could be a hub for the entire community. By allowing learners to take part in the administration of the institution and directing most expenses towards learning, this innovative university would foster a culture of continuous education. And it wouldn’t be limited to traditional campus settings – learners could gather in public spaces such as libraries, museums (think of the MET that had its own school), and cafes, making the university a shared resource for all. But this is just the beginning – this university would see itself as part of a larger commonwealth of co-operatives that includes student housing co-ops, food co-ops, and even taxi-platform co-ops. The potential for collaboration and growth in such a scenario is limitless.

A co-operative university that is governed by an elected board and allows for all members to vote on important decisions would be an empowering model. With instructors acting as learning coaches, and the inclusion of non-traditional faculty members with diverse backgrounds and qualifications, this institution would be a beacon of inclusivity and innovation. And by fostering intergenerational learning through the inclusion of learners from different age groups, such as pre-college students, traditional university students, and retired professionals, this university would create a rich and diverse learning environment.

The co-operative university of the future may well be a decentralised federation, taking advantage of the versatility and effectiveness of hybrid learning. Faculty could live anywhere in the world. Enabled by platform co-ops, it will support and empower local learning circles in cities and rural areas across the globe, ushering in new forms of education.

As learners in a co-operative university, it is only fitting that the digital platforms we use should reflect the co-operative principles that define that institution. These platforms should not be owned by large tech companies, but rather be accessible and controlled by member-owner-learners who have a say in their operation. By demonstrating the value of a democratic internet and promoting collective control and access to data, we can empower learners to become active and responsible members of their learning community.

It is exciting to contemplate the potential of a cooperative university, but it is worth noting that there are already several functioning models to draw inspiration from. I, for one, am grateful to have had the opportunity to work in one of these innovative institutions for many months.

Existing cooperative universities, such as those in the Basque country, Kenya, and Colombia, offer a refreshing alternative to the traditional American higher education model but they are not a learner paradise either. They are not without their complexities. These institutions represent a departure from the traditional American higher education model, with a structure that organises departments as worker co-operatives and establishes the Provost Office as a second-level co-op with representatives from the various co-operatives. In some cases, pay ratios are implemented to ensure that the president’s salary does not exceed six times that of the lowest-paid full-time worker.

In short, there is lots to love. But while co-ops have proven their value in many sectors, they have yet to gain traction in higher education. One possible reason for this is that stakeholders may struggle to commit to the level of involvement required. The “democracy muscle” does not automatically flex; it must be exercised and developed through active participation; it requires commitment, time, and energy.

If we hope to bring about significant change in higher education in the U.S. through the co-op model, we must be prepared to pay a price. This means that it may be necessary to secure grants to be able to do any research and that pay may be lower and involve much more teaching. A different university is possible, but it will not be as easy as just adding the fair pay and democratic governance we crave to everything we currently love about our existing universities.

The mass demonstrations at UC Berkeley and The New School represent only a tiny fraction of a global effort to envision the future of universities. Let us not just envision a better world, but also take action to build it. The co-op model may not be the sole answer, but it is a promising one that deserves our attention as we strive for community self-governance. By coming together, we can shape a university that is affordable, inclusive, decolonized, and anti-racist, serving the needs of all who depend on it.