Farmers are on the frontline when it comes to climate crisis: it threatens increasing disruption to their operations and at the same time puts them under huge pressure to cut emissions – while increasing production to feed a growing population.

It is often said that co-operation is a necessary response such crises: and in that spirit, this year’s conference of the Scottish Agricultural Organisation Society (SAOS), held in Dunblane last week, was devoted to the challenges of net zero.

First up to speak was Mike Robinson, chief executive of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, who chaired the Scottish government’s independent Farming for 1.5° Inquiry to find out how the agriculture sector could meet its obligations to keep temperature increases to 1.5C. During this process, one farmer told him: “There’s no such thing as climate change so we’re wasting our time”.

But, said Robinson, this no longer matters: scientists accept the threat of climate change, as do governments, farmers unions and consumers, who are demanding sustainable food. “This is an inevitable direction of travel,” he said.

For farmers, cutting emissions is in their own interests, he warned. While warmer temperatures bring some benefits like a longer growing season, the risks – such as increased risk of storms, drought, flood, pests and crop disease – massively outweigh them.

And government wants action from farmers, he added: agriculture makes up 11% of UK climate emissions – 18% for Scotland – and while the industry has made impressive reductions in the past, this has slowed in the last 10 years. “Scotland will not hit its climate targets without agriculture and land use delivering,” said Robinson.

It’s important to see agriculture as a solution rather than a problem, he said, noting the commercial advantage in getting on board with the process early. Giving an example of financiers who got their fingers burned by failing to realise their coal investments would lose value, he said: “If we took climate change on board, we’d be market-prescient and prepared for future.”

This was echoed by the second speaker, Andrew Niven from Scotland Food and Drink, who noted the growing urbanisation of the human population around the world. This has provoked a sense of alienation from nature and the land which consumers are trying to remedy by focusing on heritage foods, ordering veg boxes and demanding transparency on food chain sustainability. And after a few grim years of pandemic, war, economic disruption and political division, they are also seeking solace in simple pleasures – such as enjoying food.

These trends all offer opportunities to farmers, said Niven. But while opportunity knocks, meeting the climate expectations of consumers is a tougher call. During the day a number of remedies were suggested; a film clip showed a Scottish farmer’s experiments with agroforestry, growing timber on grazing land to absorb carbon. This has the added benefit of improving animal welfare, with the trees offering livestock a more comfortable and sheltered environment than a bare field.

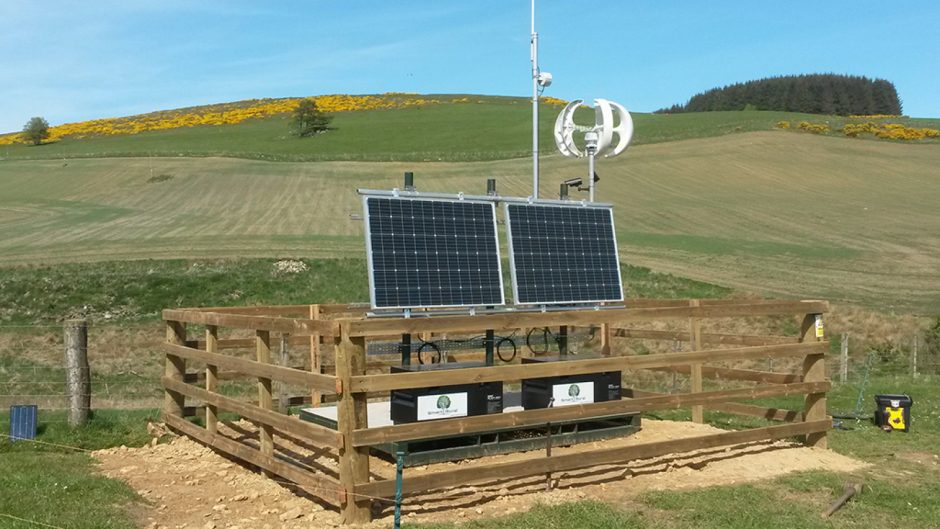

Alison Hester from agri-science researcher James Hutton Institute suggested another remedy: small scale electrolysers, which uses solar and wind energy generated on farms to create hydrogen fuel – allowing farms to decarbonise the heating of their sites and the machinery and vehicles they use.

The Institute has been awarded funding awarded funding for a feasibility study into the tech, to be run on its farm. A unit taking up 30sq m can generate 100% of the farms energy needs, said Hester. The drawback is the £6m build cost for a unit, including wind turbine – but here, she said, co-operation can help, building economies of scale and collaborating to compile a data set that will convince government to provide financial support. “There has to be incentivisatlon and support for early stage adopters,” she added.

The good news is that “everything we are using is commercially available now – it can be build-ready … it’s replicable, and has modular and scalable components”. There is also potential to create employment with the right sort of apprenticeships to develop green job skills, said Hester.

She added: “We need to work in partnership to develop this – SAOS is an important partner … SAOS and the National Farmers Union Soctland are conducting outreach action to realise its potential through co-operation and collective procurement.”

If this works, the benefits are considerable: the Scottish government wants to make Scotland ”a leading hydrogen nation” using local production hubs and a mix of public and private sector support. The tech potentially offers farms total energy independence, rural decarbonisation and – by creating hydrogen fuel – also solves the problem of intermittent energy supply.

More research is being carried out by Scottish Agronomy, a co-op formed in 1985 to help farmers increase crop production. Managing director Adam Christie repeated the message that climate innovations present an opportunity for farmers – but this came with a warning. “We are under pressure to move on this and there is a danger we will be forced to move at a rate the science can’t keep up with.”

Innovations must be tested on farms, he said, giving the example of Encera, a fertiliser hailed as a magic bullet for the problem of nitrogen use on farms: but although it worked perfectly in greenhouses, it was a failure in the field.

Moving forward, Christie said farmers must concentrate on people and planet – and also profit, or they will go out of business; on that score, the soaring costs of nitrogen provide an extra incentive to find an alternative. With half of arable farming’s climate emissions come from fertilisers, this is important; efficient nitrogen use is the key here,he added, delivering lower emissions while maintaining production.

“There is a moral responsibility on arable farmers to make the maximum use of the land they have,” said Christie. “There’s 8 billion mouths to feed on this planet.”

There are processes that can help – tilling the land, removing or chopping straw in the soil, moving from simple spraying to integrated pest management, and the use of cover crops like oil radish to maintain soil structure.

“There is a limit to what we can do in an arable setting if we want to maintain production,” said Christie, “but there is massive pressure on the issue of climate.” Big industry customers like PepsiCo, themselves urged to act by consumers, are demanding sustainability from all their suppliers, which means that farmers “have to change”.

While there are subsidies for using unproductive land for biodiversity, they do not currently compensate for taking land out of production, said Christie. But if big businesses want to improve their profile by paying farmers to use low-yield land for biodiversity “it would be foolish of us not to get involved in that … end users are much more involved than at any time I’ve ever known in engaging with growers”.

For a benchmark in dealing with climate, Christie recommended dairy co-op Arla which is trialling green hydrogen, gene editing of plants and alternative livestock feed to reduce methane emissions. But even though Arla is “miles ahead of where we are,” Christie said its leaders have accepted they cannot face the climate challenge alone. Co-operation will be be key, and will help to stimulate new ideas.

The conference also heard from Richard Simmons of Carbon Capture Scotland, which removes carbon dioxide emitted by whisky distilleries. Some of this is put to industrial use – in the manufacture of dry ice and even the Pfizer vaccine – but there is no use for the vast bulk of the carbon generated by industry and it will have to be buried.

Simmons called for input from farmers to help drive this; in Scotland there are a million tons of CO2 that can be removed easily, he said; in the longer term, the figure rises to 4.6 million.

A staple topic at SAOS conferences is the use of farm data, and the the apex’s data and connectivity manager George Noble gave members an update on how this can be used to drive climate action.

A crucial problem is poor internet connectivity in rural Scotland, rendering data tech ineffective. Given that this tech can potentially provide data on soil quality, weather, crop yields, river levels and pollinator numbers – and allow farmers to turn on ventilation in livestock sheds if air quality drops, helping to prevent disease – SAOS is keen for this to be remedied.

It has launched collaborative businesses, such as SmartRural which is building a flexible nationwide digital infrastructure, and progress is being made. SAOS is working with national and local government to improve coverage and is running test projects on a number of farms.

Good data is vital if farmers are to demonstrate their sustainability to consumers and policymakers, said Noble. For instance, monitoring of ground moisture and river levels can show farmers the safest time to spray nitrogen fertiliser to avoid it being washed away into the river system; and energy monitoring will allow farmers to maximise efficiency.

But if all of this is to work, it has to be tailored to the needs of farmers, and Noble said SAOS needs to hear from them to learn what they want.

- This article was amended on 1 February, in the section on the James Hutton Institute, to clarify that it is the Scottish government’s ambition to make Scotland a leading hydrogen nation, and that the Hydroglen project is still in the planning stage.