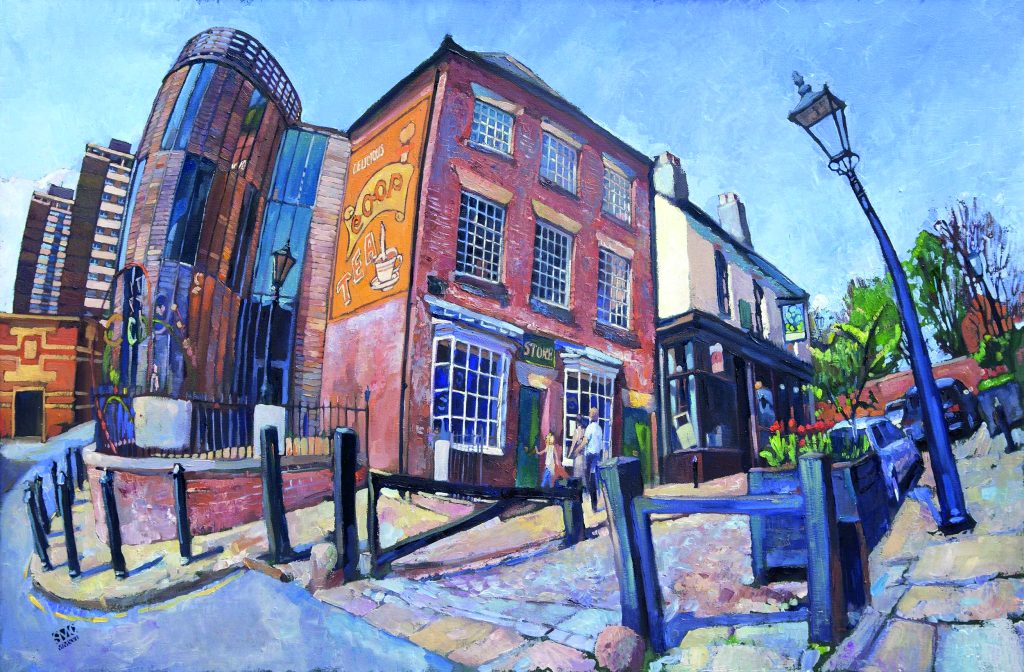

Main image: Toad Lane Co-op by Night, Xavier Pick.

On 21 December in 1844, the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society opened a small store in England with five items and little fanfare. Thus humbly began the modern co-operative movement. Let’s step back into that time to get a sense of how co-operative history was made.

In the summer of 1843, a 31-year-old Charles Dickens journeyed to Lancashire, to see for himself how life was lived in the industrial north of England. To feed his journalistic curiosity, he visited a workhouse in Manchester to see how the poor were surviving the “hungry forties”. Dickens was taken aback by the terrible conditions he saw in the midst of the burgeoning wealth. In the bustling heartland of the Industrial Revolution, he saw the two Englands of rich and poor.

The next day, speaking to an audience of well-to-do aristocrats and mill owners at Manchester’s prestigious Athenaeum Club, he urged the audience to overcome their ignorance which he said was “the most prolific parent of misery and crime”. Dickens asked them to take action with the workers to “share a mutual duty and responsibility” to society.

On the train back to London, impacted greatly by the poverty and misery he had seen, he conceptualized A Christmas Carol. He began writing the classic tale a week later and completed it in six weeks. The book was published on 19 December 1843, and Christmas was never the same again.

On the eve of revolutions throughout Europe, Dickens counselled that hearts must hear and eyes must see for society to change. In his mind, the Bob Cratchits and Tiny Tims of the world would have to wait for the Ebenezer Scrooges to literally go through hell before heaven could be made upon Earth. Dickens would return to the Lancashire mill towns to gather information for another novel, Hard Times. The solution in much of his writing was the voluntary transformation of the rich and powerful.

But A Christmas Carol was semi-autobiographical, shaped by Dickens’ memories of father’s time in debtor’s prison and the suffering within his own family. It was also a social commentary on the tremendous conflicts transforming British society from top to bottom as a result of the Industrial Revolution.

Life did not follow art, however: Scrooge’s peaceful transformation was not repeated enough by a self-interested industrial aristocracy. Five years later, revolutions occupied centre stage in much of Europe.

In the summer of 1843, at the time Dickens was visiting Manchester, a group of Bob Cratchits and their spouses were meeting regularly just 11 miles away in Rochdale.

One of those Pioneers, John Kershaw, recalled a key step in organising the co-op, writing:

“A few days before Christmas, 1843, a circular was issued calling a delegates meeting to be held at the Weavers Arms, Cheetham Street, near Toad Lane.”

At that meeting, the Rochdale families decided that rather than wait for the mill owners to do something for them, they would have to do it for themselves. It took the determined mill workers about a year before they had collected enough of their meagre savings to open up their small co-operative store.

Their immediate aim was to get better quality food at decent prices, and provide some members with jobs. Their ultimate goal was to use the co-op’s profits to create their own community where working and living conditions would be better. Among the satanic mills of William Blake they would build their New Jerusalem.

Winter Solstice, 21 December, was the longest night of the year. Under the old Gregorian calendar, it was also Christmas Day. The Pioneers opened their co-op on that date – a Saturday – in 1844, almost one year to the day after the publication of A Christmas Carol. However, for the members of the newly formed Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society, the holiday season would not be one of gifts or gaiety but of consternation and caution.

On that Saturday, at 8pm, a small group of the Rochdale Pioneers and their families huddled together in the shop to witness the store’s opening. The temperature was below freezing, made worse by the damp in the almost empty warehouse at 31 Toad Lane (T’Owd is Lancashire dialect for “the old”) in Rochdale. Outside on the busy street they could hear the clattering of wooden clogs on cobblestones, as tired mill workers hurried home to find warmth from the winter’s chill. As the church bells across the street struck the appointed hour, the founding members heard each chime with beating hearts. Then, James Smithies went outside and bravely took the shutters off the windows.

With the final shutter removed and a few candles lighting the store’s bay windows, the modern co-operative movement began. This little shop in Rochdale, England, would be its lowly birthplace and these humble hard-working families its founders.

When the co-op opened there was no ceremony or cheering to be heard, only the jeering of the “doffer boys” laughing at the silly idea of it all. The “doffer boys” were the mischievous factory lads of the era. The shop was, by their account, a daft dream of weavers and another idealistic experiment in brotherhood bound for bankruptcy.

On the almost bare counter were proudly yet sparsely arranged the co-op’s five items for sale; six sacks of flour, one sack of oatmeal, 2 qrs. of sugar, 1qr. 22lbs of butter and two dozen candles. The entire stock, worth 16 pounds, 11 shillings 11 pence, could have been taken home in a wheelbarrow. The ground floor they rented for 10 pounds ($18) per year measured 23 feet wide and 50 feet deep (a total of 1150 square feet). The shop itself was only 17 deep and measured 391 square feet; the remainder was used for storage and as a meeting room. Fortunately, the staunch beliefs of the Pioneers filled the sparse store with hope. This opening day would be difficult as would the next day and the day after, but their strength was their daring to dream of tomorrow.

The day before the store opened, the Pioneers supplied the volunteer staff members with green aprons and sleeve coverings the same shade of green used by the Chartists. Many of the Rochdale Pioneers were Chartists, a people’s movement for political rights and democracy in Britain. At that time, Parliament gave voting rights only to property owners. In 1840, the census showed that Rochdale had a population of 24,423. Of that only about 1,000 inhabitants could vote. Two million people signed the Chartist’s petition to Parliament. After the petitions were rejected, the disappointed Rochdale Chartists turned to self-help and co-operation; the sad ending of one democratic movement gave birth to the success of another.

On the day the co-op opened, membership in the Rochdale Pioneers numbered 28. Most of the Pioneers invested a share of one pound each (equivalent in 1844 to two weeks’ wages). They had drawn up their principles and rules of operation which combined a utopian purpose and useful practicality. The need appeared so great that nothing but something powerful could change their circumstances. These weavers had dreams and what is more they were going to do something about them.

The co-operative idea soon took hold in Rochdale and nearby towns in Lancashire and Yorkshire. In town after town, the Bob Cratchits of England joined their local co-op and lent their skills, optimism and idealism to the fledgling organisations and the Bess Cratchits’ lent their money management, organisational capacity and determination. For the first time in their lives, the women of England had a vote of their own in a co-op of their own. Life in England changed dramatically when millions of families owned their own co-op stores, factories, houses, a co-op bank and an insurance company – just as the Rochdale Pioneers had dreamed.

Now, as in 1844, people on every continent are using their co-operatives to meet their needs for food, credit, housing, health, work, enterprise and community. Co-operatives continue to help develop people and communities, economies and democracy following the seven principles of the International Cooperative Alliance.

Starting in the autumn, candles are lit for Christmas, Chanukah, Diwali, Kwanza and other festivals. Around the world, people in different languages and different faiths pause for a moment to give thanks for family, fellowship and a better life. Dickens said it so simply through the words of Tiny Tim, “God bless us, everyone!”

The Rochdale Pioneers would be proud of their legacy of economic and social justice. The candles that gave light in Rochdale that night now shine strongly all around the world. The co-operatives and credit unions serving over one billion families worldwide are strengthening communities everywhere. In their honour, the United Nations has declared 2025 the International Year of Cooperatives.

And in Rochdale during the holiday season – and especially on 21 December – the Victorian gas lamp outside the original co-op store on Toad Lane seems to shine a little brighter. It is on this very night that the lights were lit.

David J. Thompson is author of Weavers of Dreams: Founders of the Modern Cooperative Movement, Co-opportunity: The Rise of a Community Owned Market, co-author of Cooperation Works and A Day in the Life of Cooperative America and has written over 400 articles about co-operatives. He was born in Blackpool, 50 miles from Rochdale. David was inducted into the US Cooperative Hall of Fame in 2010. He lives in Davis, California and is President of the Twin Pines Cooperative Foundation, sponsor of the Cooperative Community Fund Program, the largest provider of investment capital to co-operative development organizations in the USA (community.coop)

This article is copyrighted and not to be reprinted without the author’s permission.