Carl Giles is best known for his decades-long career with the Daily Express and Sunday Express newspapers, which saw him become one of the country’s most popular cartoonists.

But – despite working for Conservative newspapers, a love of the finer things in life that saw him drive a Bentley, and the apolitical tone of his work – Giles was a committed socialist. And he spent his formative years as cartoonist for the Reynold’s News, a left-wing Sunday paper owned by the Co-operative Press.

This phase of his career makes up the bulk of a new book of his cartoons from World War II, edited by Dr Tim Benson, an expert on political cartoons.

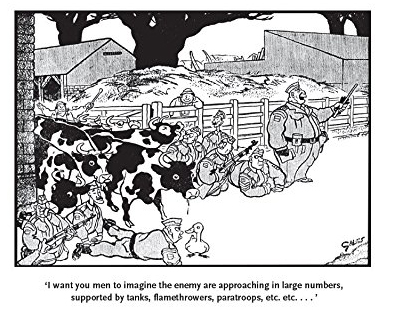

In his introduction to Giles’s War, Dr Benson says the cartoonist originally set out to work as an artist on animated films – and the influence of this remained in the detailed single-framed cartoons that won him fame.

This style was honed during his time with Reynold’s News, which began printing his work in 1937 and was to present him with the challenging subject matter of the war.

His work for the paper also featured a fictional version of himself, Young Ernie, a forerunner of the Giles family characters of his postwar work.

“Giles’s earliest cartoons at the Reynold’s News already contained the energy and wit that would make him famous,” writes Dr Benson.

“Giles later called is wartime work ‘primitive’ compared to what came after, and at times this was certainly true. However, towards the end of the war one can see that he had already honed his skills as an accomplished draughtsman.”

The war solidified his political allegience to the Reynold’s News, as he shared the paper’s dislike of prime minister Chamberlain and his policy of appeasement.

And this shared politics saw him make life-long friends among colleagues at the paper, and also write several articles.

But he soon felt he had outgrown the co-operative Sunday title, which offered a lower salary than its daily rivals and also had less space to run his cartoons. And, in October 1943, he switched to the Express where he would spend the rest of his career.

“Giles either felt guilty about resigning from Reynold’s News,” writes Dr Benson, “or was made to feel so by his former colleagues, who believed he had sold his soul to the Tories. This reaction hurt him deeply.”

Giles would seek to defend what he called his “Judas act” – and also declined to correct rumours that Reynold’s News had cut down his work to free up space, and claiming he had been headhunted by the Express when in fact he had approached the paper himself.

His departure was met with sorrow by Reynold’s News readers, Dr Benson notes, and even prompted one forlorn reader to send in a poem which asked “tell me, oh why have you robbed us of Giles?”

Giles’s War collects nearly 150 of his cartoons for Reynold’s News, along with his later efforts for the Express.

The cartoons offer a vivid portrayal of the war years, of Giles’s formative years, and of a brief chapter in the history of co-operative journalism, when it boasted a future icon among its ranks.