As the UK prepares to exit the European Union, it is worth re-examining why the co-operative movement had mixed views about the common market.

In spite of joining the Common Market under Ted Heath’s pro-European Tory government in 1973, the UK maintained a sceptical approach to the European project.

Back then the European Economic Community (EEC) comprised only six states: Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany.

How did the EU come about? Treaties of Paris and Rome

The current union of 28 states dates back to the creation of the European Coal and Steel Committee in 1951 following the signing of the Treaty of Paris. The six states created a common market for coal and steel to neutralise competition between European nations over natural resources. The idea for the committee had come from French foreign minister Robert Schuman, who wanted to make war in Europe “not only unthinkable but materially impossible” by interconnecting the countries’ economies.

The EEC was established in 1957 with the signing of the Treaty of Rome, which proposed to create a single market for goods, labour, services, and capital across the EEC’s member state. It also suggested the creation of a Common Agriculture Policy, a Common Transport Policy and a European Social Fund, and established the European Commission.

Related: Euro Coop to keep a close relationship with UK after Brexit

Britain had been invited to participate in the talks that shaped both treaties but it refused to substantially engage in these discussions on the grounds that it preferred to focus on maintaining its trade relationships with Commonwealth nations. It also wanted a global order in which the sterling was a central currency. The consequence of not being involved in setting the agenda was that by the time it did decide to join the rules had already been made.

A divided co-op movement

On 4 September 1971 a special congress of the Co-operative Union was called to determine the Co-op movement’s attitude to Britain’s entry into the EEC.

The movement was worried the UK’s admission to the common market would result in higher food prices and an increase in the cost of living. The congress was also concerned that British people should be fully aware of all the facts before making up their mind.

While the Union’s Central Executive had put forward a proposal that aimed to establish the support of the movement to entry to the EEC, an amendment designed to achieve the opposite outcome was also debated. The Central Executive’s proposal was backed by the Co-operative Party and the CWS.

Delegate B T Parry, who moved the proposal on behalf of the central executive, which he chaired, said at the meeting: “We are a highly industrialised country, depending upon our exports of manufactured goods for our continued economic existence – industry, therefore, will have the opportunity as never before of exploiting a vastly increased home market. Let me say that if British industry cannot compete inside the market, it will not for long be in a position to compete outside the market either. Let there be no dubiety.

“Unless Britain’s industry is successful, retailing, in which we, as co-operators, are principally involved, can never flourish. Of our 13m members a great majority earn their living in the manufacturing process. We have, therefore, a strong vested interest in the success of industry.”

He added that countries in the EEC had a lower unemployment rate than the UK, which had 900,000 people out of work at the time. He believed the reason for the EEC’s lower rate was the fact that the growth of the Gross National Product depended largely on investment. The countries of the Community invested 24% of their GDP between 1959 and 1969 while Britain had invested only 17%.

Workers in common market countries were also earning more than those in the UK, said Mr Parry. He explained that between 1958 and 1969 the real earnings of workers in the UK had increased by less than 40% while in the EEC they had risen by over 75%. While entry into the market was not free, he believed the UK’s GDP would have also gone up, striking “a fair bargain.”

Mr H Kempf, chair of the Co-operative Party, said: “Economic events will not wait for more committees and inquiries. We have been already talking about this subject for 10 years in the British co-operative movement and, in my view, now is the time for decision. Nor can we wait for a Socialist Europe. Our people will be better served in the long run if we join now and help to build on the foundations already laid.

“The weaker socialist and trades union movements can be encouraged and strengthened by our participation. We all wish to know the facts. But the facts of economic success, higher wage rates and standard of living are known. We all wish to know the terms. These are now known and the Executive doubt they will be improved by our remaining outside.”

Related: Co-op Group joins retailers warning against no-deal Brexit

Another delegate, Mr G Edyvane, noted that Rolls-Royce had gone bankrupt by entering into a “suicidal contract” to break into a foreign market. “Had Great Britain been able to become a member of EEC 10 years ago, the wider market would have been available and there is little doubt that Rolls-Royce would today still be one of our national symbols of excellence.”

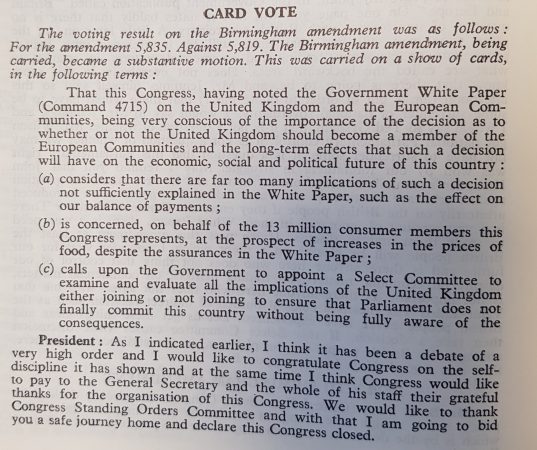

The anti-market amendment was defeated but another amendment was carried providing an escape route for those who did not support the proposal of the Central Executive. The amendment warned that there were too many implications of such a decision, which were not sufficiently explained in the government’s White Paper. It called on the government to appoint a select committee to examine and evaluate the implications of the United Kingdom joining or not joining to ensure “the Parliament does not finally commit this country without being fully aware of the consequences”.

The Birmingham amendment was carried with 5,835 votes for and 5,819 against.

During the debate on the course of action Mr D Ainley, who introduced the anti-market amendment, said Britain should not enter the EEC under the terms in the then Tory government’s white paper.

Mr A Walker from Central and East Fife seconded the amendment. He argued the movement had for a number of years been concerned about the Commonwealth, particularly New Zealand and the sugar producing countries, partners in EFTA, the freedom of the British governments to control the economy and extend social ownership, the value added tax, the agricultural support policy and cheap food and British sovereignty.

Mr C N Greenfield added: “The Common Market: we have got to understand what it is. It is a close economic, capitalist, political and military grouping. It is anti-democratic, anti-working class, anti-socialist and anti-co-operative. It exists with the object of creating a giant aggressive power grouping to promote the interests of big businesses in their search for super-profits.”

Delegates at the meeting also criticised the common market’s Value Added Tax (VAT) system, which, they feared, was to be introduced in the UK as well post joining. Indeed, after becoming a member of the European Economic Community, the UK replaced the Purchase Tax by Value Added Tax on 1 April 1973. The movement was against the introduction of indirect taxation because it believed the less well off would be more affected by it than those wealthy.

Writing for volume 45 of the Co-operative Review, parliamentary secretary of the Co-operative Union, J M Wood explained that VAT had become the most common form of indirect taxation in Europe and had been adopted by countries in the EEC, as well as other states outside the common market.

Mr Wood was also the one to receive Edward Heath’s response to the request of the Co-operative Union Special Congress to set up a select committee to enquire into the various aspects of joining or not joining the common market.

The letter said the prime minister was “sorry” to learn that the motion in favour of British entry into the EEC had not been carried and that ministers were justifying their policies within the House of Commons thus a select committee was not necessary.

Another key concern for co-ops was the ability to offer cheap food post joining the EEC. A 23 October 1971 article by Mr Wood looked at whether joining the EEC would mean an end to cheap food in Britain. He explained that while the nation had been self-sufficient in terms of food production up until the middle of the 19th century, it had later decided to specialise in provision of industrial products and services and buy food from America or Australia.

“It is usually assumed that if we do not join the EEC we shall continue to enjoy cheap food from our traditional suppliers. This assumption takes no account of the vulnerability of the British consumer to world conditions,” he wrote.

Differences of opinion meant that the movement lacked a clear common policy on the EEC.

“We are in the situation of not having a firm decision pro-market. We are in limbo,” commented Sir Robert Southern, the general secretary of the Co-operative Union in an article published in Co-op News in November 1971.

The paper played a key role in covering the debate dividing the UK co-op movement. The 13 November 1971 Co-op News issue reports how the 15 MPs of the Parliamentary Co-operative Group voted – eight against entry to the common market while six for entry and one abstained. In the House of Lords four members voted for entry with one voting against.

In the run-up to the UK joining the common market, Co-op News articles also looked at issues such as fighting inflation, opposing VAT and freezing prices.

The paper was a source of information about what was happening with co-operative movements in European countries as well. An article published on 15 September 1972 looked at Norway’s referendum on whether to join the common market or not.

Britain unable to join

Becoming a member of the common market was in itself a lengthy process for the UK, delayed by opposition from France’s president, General Charles De Gaulle.

He vetoed Britain’s membership application in 1963 and 1967 arguing that the British people were hostile to the European project and had to change their mind-set if they wanted to join. He also thought the country was too close to the US.

Following his fall from power in 1969, Britain re-applied to join and was eventually accepted, becoming a member on 1 January 1973, by which time De Gaulle had died.

A fait accompli

In 1972 Co-op News also ran a series of articles under the tagline Inside Europe – these looked at the co-operative movement in different European states, from Italy, Luxembourg or Holland. “Meet your EEC colleagues,” read one headline.

Similarly, an article from 22 September 1972 reports how the British co-operative movement was to join Euro-Coop when Britain entered the Common Market in January 1973. The decision had been taken at the Co-operative Union Central Executive meeting.

An analysis by Paul Kemezis in volume 46 of the Co-operative Review from September 1972 explored the changes in Europe’s high streets. He writes about Europe being a high-consumption society on the American pattern. The article adds that the need for Europe to consolidate and harmonise national tax systems, health and safety standards, anti-pollution laws and other business standards to create a real common market offered a broad field for regulating arbitrary corporate power.

Societies started engaging with other co-operatives in EEC states. On 8 September 1972 an article published in Co-op News described how Brighton society was arranging a visit for 20 French co-operative directors to explore retailing in common market countries.

Quoted in Co-op News, society member relations officer Don Ranger said: “Equally important is the fact that we have arranged a return trip to Rouen to study at first hand the methods of retailing in the Common Market countries. In many respects they are more advanced than in this country and so we hope for great benefit from this exchange.”

On 19 January 1973, Co-op News featured an interview with the then general secretary of the Co-operative Union, Clarence Hilditch. He said that although the movement had been split down the middle in terms of whether to join the EEC or not, as this had become a “fait accompli” so the CWS, SCWS and the central executive decided it would be in the interest of the movement to join Euro Coop. He explained that Euro Coop had direct contacts with the EEC to ensure the British movement’s policy and opinion was reflected in Euro Coop’s overtures to the EEC Commission.

As shown by Mr Hilditch’s comment, the country’s co-operative movement was not fully committed to the European project but eventually came to terms with joining for fear of being left behind. It is no surprise that the Brexit debate continues to generate mixed views.