The question of public service mutuals as a response to austerity came under scrutiny at the Ways Forward conference in Manchester, with Labour Party members and trade union representatives warning against “the marketisation of co-ops”.

The workshop, Co-ops, Solidarity and Austerity Cuts, heard from supporters of the initiative, looking at examples such as the Preston model of local procurement.

Debbie Shannon, from Link Psychology Co-operative described the “crisis” in public services in the wake of the 2010 austerity measures. When her educational psychologists department was outsourced from the local authority it was decided the co-op model “ticked all the options” in terms of delivering social value.

From there she got involved in the Preston model, with two prongs – targeting procurement to deliver social value and support the local economy, a move which kept £200m in the Preston area in 2015/16; and forcing the growth of co-ops to fill the gaps in supply chains of anchor institutions.

She said programmes like the Preston model face three important tasks: creating infrastructure to support co-ops, bringing about a culture change, and promoting the idea of co-operatives to the public. “What is a co-op? People don’t know,” she said.

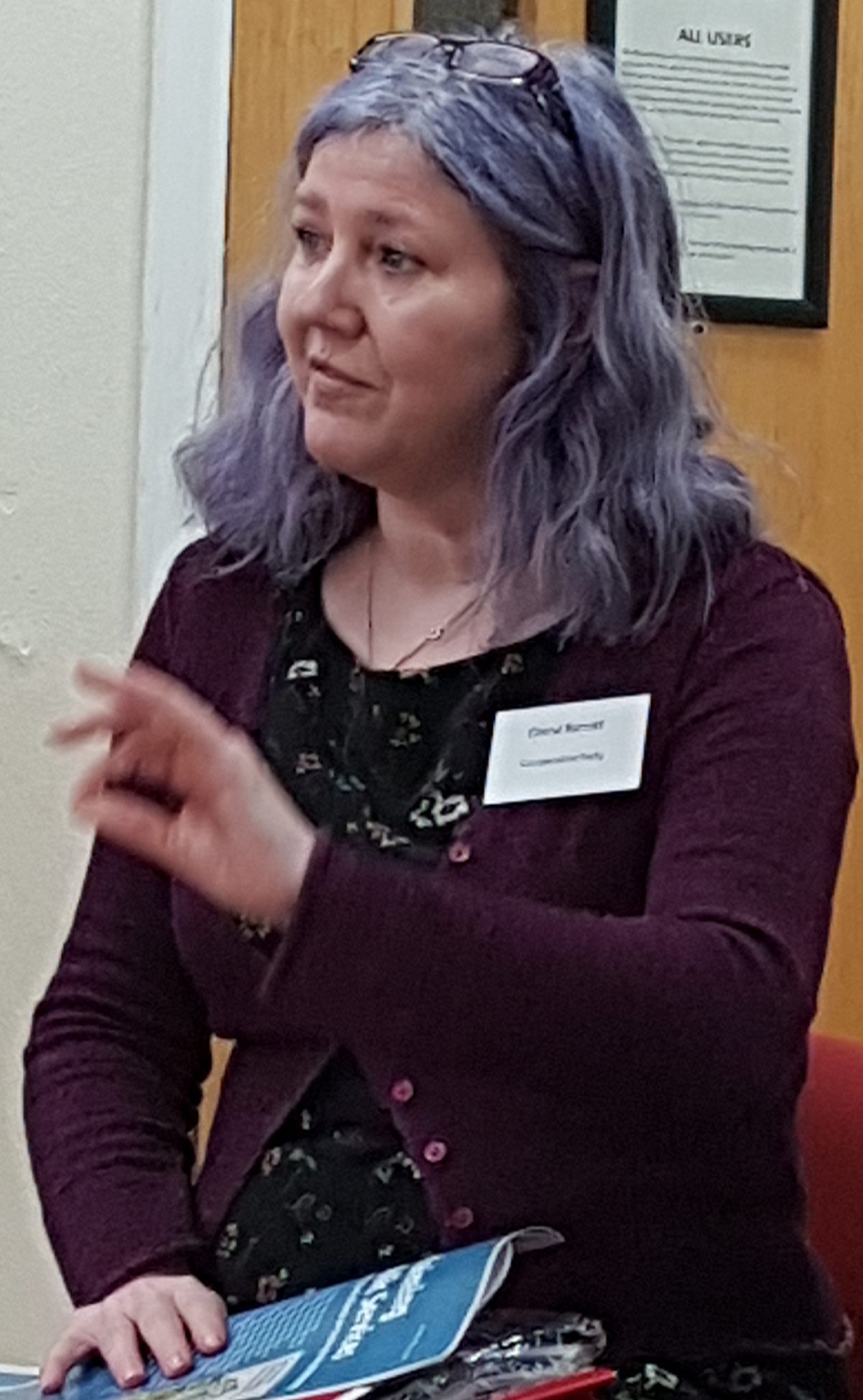

But other speakers sounded a cautious note about the idea of public service mutuals. Cheryl Barrott, a member of the national executive committee of the Co-operative Party and co-director of Change AGEnts, warned: “We need to make sure that co-operation is not used to privatise the public sector.”

But, she added, the loss of expertise lost to the public sector through job losses since austerity measures began in 2010 meant it would be hard to recreate the old model, and in any case, “there is not the appetite among the public to have a big, state-y sector”.

Which, she said, begs the question: “How do we put the public back into the public sphere?”

Paul Bell, a national officer at public services union Unison was more sceptical. He said, as a member of the Co-op Party and Midcounties, that he was sympathetic to co-ops – but also that his union was “in favour of in-house services”.

He said privatisation of public services always hit the terms and conditions of the workers, added: “The big problem trade unions have with co-ops is with public service mutuals.

“Under public procurement rules, after three years, public service mutuals have to compete with the likes of Capita and Circa and there’s a race to the bottom.

“How does the co-op movement add value to workers who want terms and conditions, and social mobility?”

He added: “Mutualising the private sector is better – we support that for Carillion, for instance.

“But the public sector is already co-operative because we own it.”

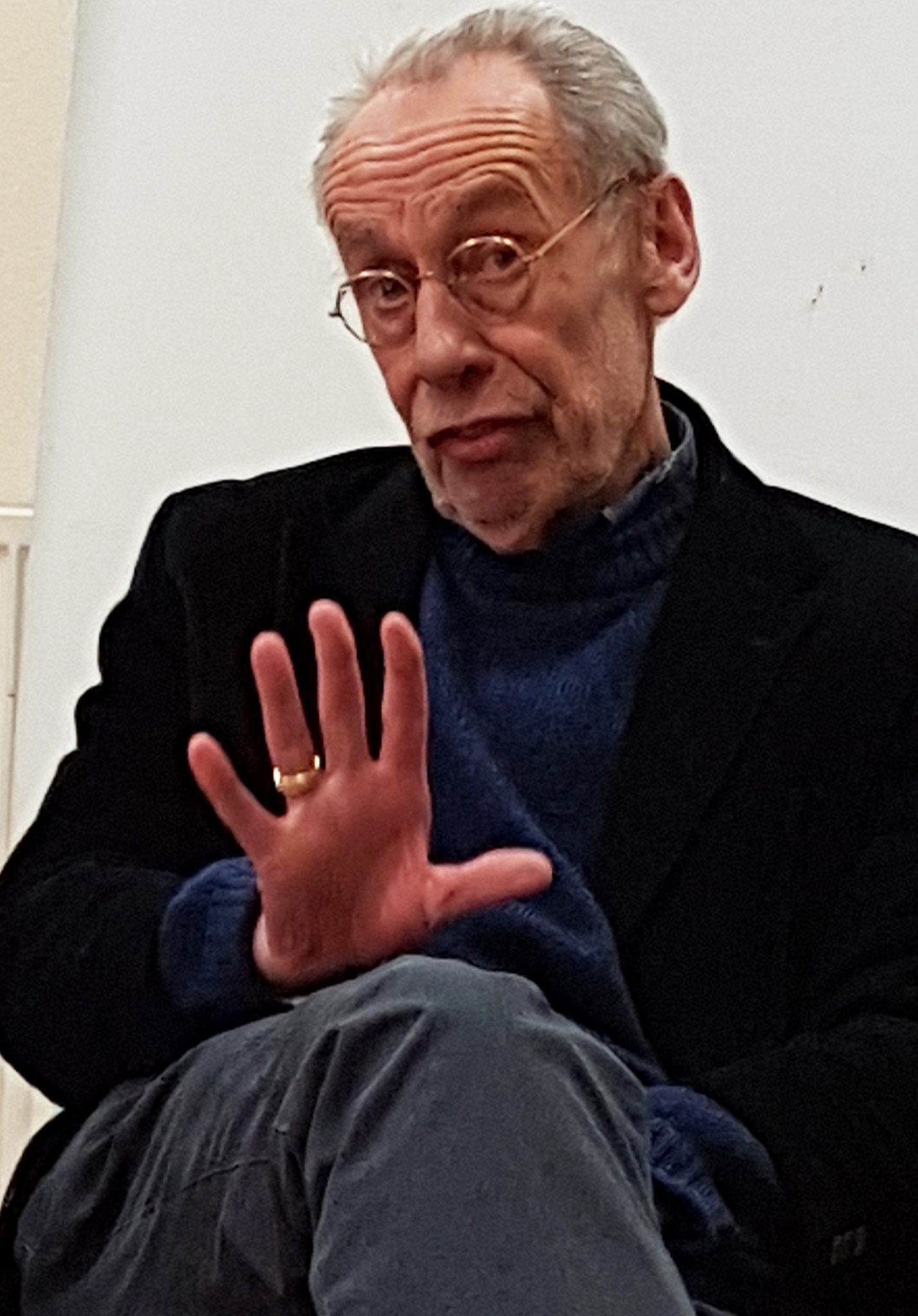

There was more opposition to public service mutuals from Les Huckfield, a former MP who now works with Aizlewood Group, which was formed to contribute to the debate around public service mutuals and resist privatisation within the public sector, specifically in local government.

He said there had been a previous attempt to build a public sector based around common ownership, under the Labour government in 1976, which set up 60 local co-op development organisations around the UK.

“It created something like 2,000 co-ops of various shapes, sorts and sizes in the 1970s, 80s and early 90s,” he said.

“But today we are not talking about an expansion of co-ops in the same dimension. We are talking about an expansion of the co-op sector mainly by privatising public services. Many of us have a problem with that.”

Echoing Mr Bell’s warning on the effects of competitive tendering, he said: “Whether it’s a co-op, a social enterprise or third sector, they will have to go through competitive bidding – and the only way they’ll land that job is by cutting people’s wages, terms and conditions.”

And he warned that outsourcing threatened the “redistributive element” of public services as well as the “democratic control over the delivery of those services”.

After the speakers had finished, the discussion was thrown out to conference delegates. John Boyle, party support and principle six officer at the Co-op Party, took issue with the criticisms of public service mutuals.

“I don’t share your lack of enthusiasm about co-ops being capable of winning contracts,” he said, citing successful examples such as Shepshed Carers in Leicestershire, which enjoys “a minimal turnover of staff”, and a school meals co-op formed by Plymouth Council.

And he argued that co-ops are more democratic than councils because they are run by members who have a concern in the services being run rather than local officials, and takes out the profit motive needed to support shareholders and highly paid chief executives and managers.

The 2012 Social Value Act was drafted to ensure the procurement process took into account “economic, social and environmental wellbeing.” Mr Huckfield had pointed out that this was often ignored during the bidding process but Mr Boyle said the onus was on the co-op movement “to challenge procurement officer so ensure the Social Value Act is held up”.

But Cheryl Barrott warned that there was “a £2.5m deficit in care” and if co-ops were forced to carry out the effects of that deficit, “It could destroy public faith in co-operation”.

She added: “We have to look at what works well – such as small, boutique co-operation. Who can afford this? How does a homeless person afford co-operative housing? A redistributive effort is needed.”

She called for a Faircare Marque to maintain care standards and for the regulation of standards in co-owned, democratically controlled multistakeholder co-ops.

Debbie Shannon defended the public sector mutual model, pointing out that the Preston procurement model enabled it to keep £200m in the local economy.

And Pat Conaty from Co-operatives UK said: “The primary issue is getting those corporations out who have been starving social care of funds. If we set minimum standards, unionise the co-op sector, we could work together.”

But Mr Huckfield countered: “We do not want to see co-ops in a market setting. Co-ops should be an alternative to the market.”

And Paul Bell said: “It’s not my job to criticise co-ops, it’s my job to say there’s not enough money in the system. It doesn’t matter who provides the service. From a trade union perspective, it’s the workers who suffer first.”

Ms Shannon said: “No, we don’t have enough money. But in the meantime, we need news ways of doing things. Co-ops are about social value and social responsibility.”