The Co-op Group has launched a scheme to help survivors of the modern slave trade restore their lives by offering them paid work.

Police estimate there are more than 10,000 people in the UK who have been forced into slavery – including prostitution, domestic service and forced labour.

The scheme aims to help those who have escaped this horrific ordeal by giving them a four-week paid placement with the Group. At the end of this, if their trial has been successful and a post is available, they will be given a non-competitive interview for a job.

The Group has teamed up with charity City Hearts – and is planning to work with others – on the Bright Future project, which will help 30 survivors this year.

One of the architects of the scheme is the Co-op’s group policy and campaigns director, Paul Gerrard. He says it goes to the heart of the Group’s Values and Principles but wants other businesses to follow suit.

“This is very much a case of supporting the survivors of modern slavery so they can get back the lives people have stolen them,” he says.

“People often think that slavery is something that happened a long time ago, or a long way away, but police estimate there are 10 to 15,000 slaves in the UK right now. Some of them were trafficked here, some are UK nationals.”

One survivor has already been taken on as colleague by the Group, he says, under conditions of strict anonymity. Counselling will be provided by City Hearts, a charity in the north-west of England which provides help to people who have been trafficked and works to raise awareness of the problem.

Related: Group offers new life to survivors of modern slave trade

“We’re working to give people four-week places in our business with the possibility of paid work,” says Mr Gerrard. “At the end of it, if the candidate is suitable and there is a job to offer, they will be given a non-competitive interview for a post. We’re aiming to have helped 30 people by the end of the year.

“In terms of support, there is a triangulation between the store manager, the counsellor at City Hearts and the individual. Counselling is very important and we work closely with City Hearts on this.”

But, he stresses, confidentiality is vital. “When the survivor opens up and shares their story is up to them, not to us. Our priority is to retain anonymity. When, and if, they are ready they can share with us. Only the store manager knows among their colleagues – nobody else is told, nobody needs to know.

“We’re giving them the opportunity to take back their lives and City Hearts is there to offer personal support.”

The scheme extends much further than helping 30 people over the course of a year, stresses Mr Gerrard, who is hoping for a sea change in how businesses approach the issue.

“We’re in this for the long haul,” he adds. “We’ll be running with this for a number of years and we’ll be talking about modern slavery, and the reality of what that means, through our stores and to our membership.”

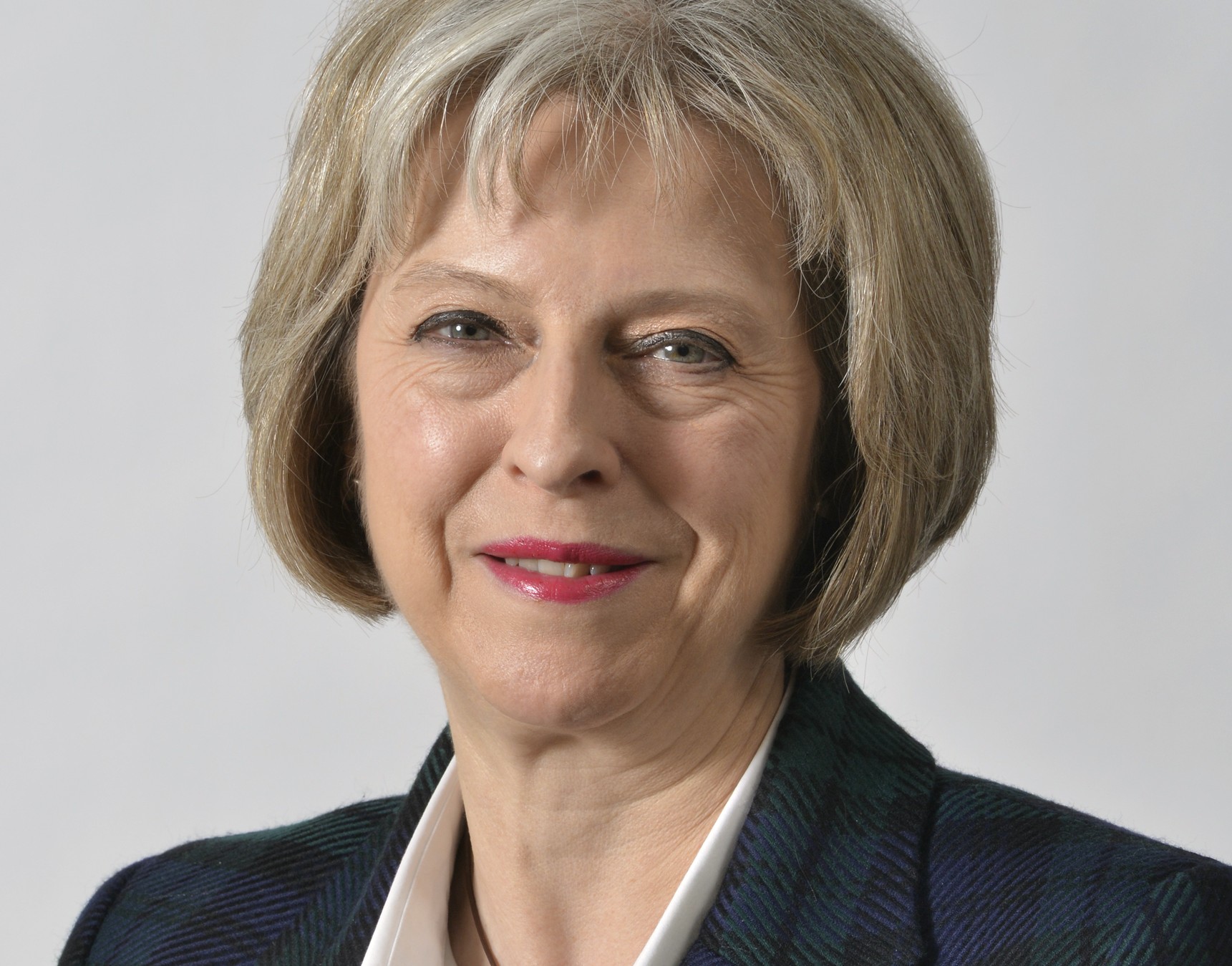

He says progress has already been made in the UK with the Modern Slavery Act 2015, pushed through by then-home secretary Theresa May. But he says there is a moral obligation for businesses to further than simple compliance with the law.

“It puts obligations on businesses to make sure it is eliminated from their supply chains but we’d been doing that for years already.

“With all our own-brand food suppliers we require visibility of what they do so we can make sure the right systems are in place in our supply chain. It’s a matter of making sure people are trained to identify and deal with cases – you can do an inspection one day a year but what happens the rest of the time?

“We work with Stronger Together and with other businesses within the UK, and throughout the world, to keep it out of our supply chain.”

The Bright Future scheme is part of the Group’s efforts to take this work further, and will extend beyond the initial work with City Hearts.

“We have a structured plan,” said Mr Gerrard. “As well as supporting people with the help of City Hearts in the north west, we are planning to work with another organisation in Yorkshire, the Snowdrop Project. We’re looking for another organisation in the south east.

“But it’s not just a case of how many people we help, it’s also a question of how many other businesses help. We have legal obligations under Modern Slavery Act but need to go further, to play our part as responsible businesses.

Read more: Co-ops and a century of ethical practice going back to the ‘soap wars’

“Other businesses need to do this too – and we will help them and share our experience with them. Over the coming weeks I’ll be speaking to other organisations, to the Chambers of Commerce and the British Retail Consortium, and to other independent retailers in the co-op sector to see if they can take up this scheme.”

He stressed that the government also has a part to play and welcomed the lead it had taken with the Modern Slavery Act and the appointment of an independent slavery commissioner, Kevin Hyland, to advise ministers.

“I’ve been speaking in London with MPs, with the Home Office, with Kevin Hyland,” added Mr Gerrard. “And the Co-op is going to keep working on this, it’s an ongoing commitment.

“It’s part of our wider human rights framework, drawn up by our business leaders and members council and approved by the executive, and we’ll be making more announcements on that before our annual conference.”

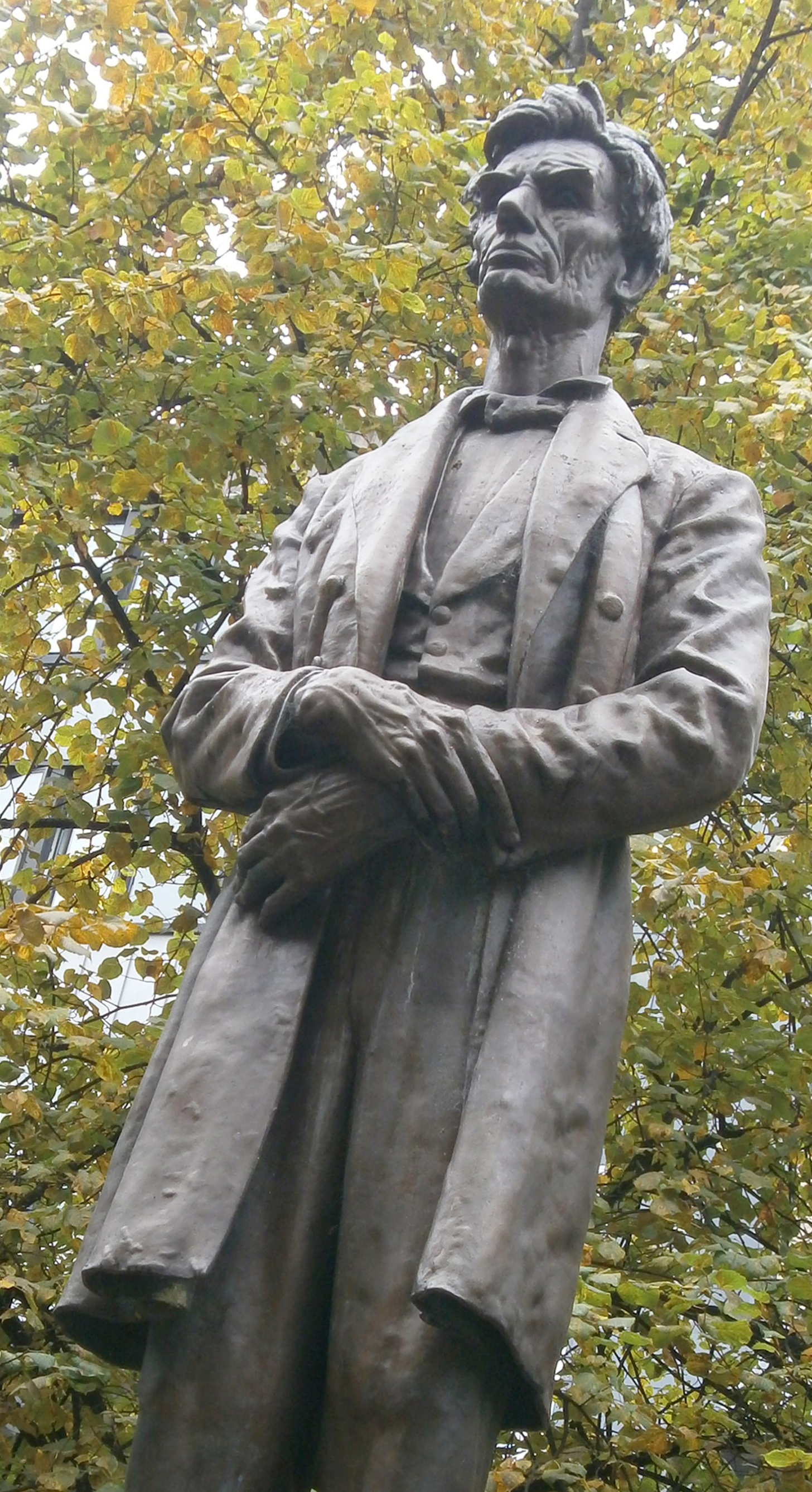

A co-op heritage that goes back to the Great Emancipator

A former history student, Mr Gerrard traces a line from the Bright Futures scheme right back to the formation in 1863 of the Co-operative Wholesale Society, which eventually became the Co-op Group.

“As a co-operative it is a fundamental part of our identity, of our Values and Principles,” he says. “The CWS was launched by abolitionists and it is part of our values and principles.

“In 1863 a letter was written by Abraham Lincoln to workers in the north west of England, after 5,000 men and women had gathered in the Free Trade Hall in Manchester to support him against slavery, telling him ‘keep doing what you’re doing’.”

But this was at terrible personal cost to those workers, coming at the time of the Manchester cotton famine.

“Lincoln had blockaded the southern ports of America to stop the cotton going out – and this hit industry, which relied on that cotton, in Manchester and the surrounding districts,” says Mr Gerrard.

“It was one of the worst humanitarian disasters of the industrial age. Men and women were literally dying of hunger.”

Despite this hardship, men and women gathered in the Free Trade Hall to support Lincoln.

“Two of those men, within months, went on to form the CWS,” says Mr Gerrard. “Two of the people behind that act of heroism were people who formed this co-op.”

In their letter to Lincoln, the workers at the Free Trade Hall wrote: “The vast progress which you have made in the short space of twenty months fills us with hope that every stain on your freedom will shortly be removed, and that the erasure of that foul blot on civilisation and Christianity – chattel slavery – during your presidency, will cause the name of Abraham Lincoln to be honoured and revered by posterity.

“We are certain that such a glorious consummation will cement Great Britain and the United States in close and enduring regards.”

In response, and paying tribute to the victims of the famine, Lincoln said: “I cannot but regard your decisive utterances on the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country.”

In 1918, a statue of Lincoln was erected in Platt Fields Park, Manchester, which moved to Lincoln Square in the city centre in 1986.