As Unesco adds 17 buildings by Le Corbusier to its list of World Heritage sites, David J Thompson reveals how the revolutionary architect created a vision for co-operative living in the ruins of postwar France. David is President of the Twin Pines Cooperative Foundation in the United States. He has an MA in Architecture and Urban Planning and visited L’Unité in Marseilles in 2004.

In July 2016, Unesco added 17 buildings by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier to its list of World Heritage Sites.

Unesco said the buildings “reflect the solutions that the modern movement sought to apply during the 20th century to the challenges of inventing new architectural techniques to respond to the needs of society.”

One of the best-known buildings added to the World Heritage sites was L’Unité d’Habitation. The social housing prototype was built (1947-1952) in Marseille, France. This modern exploration of post World War II collective housing is revered by some, yet revolting to others.

As France struggled to recover from the devastation of World War II, the cities of Marseille and Nantes desperately needed solutions to re-house working people. Those cities wanted buildings that pronounced a new form of shared community in a renewed world.

The utopian city-living design developed by Le Corbusier in Marseille was replicated in the L’Unité in 1955, Berlin–Westend in 1957, Briey in 1963, and Firminy in 1965.

L’Unité in Marseille (337 apartments) was to be a new form of collective ownership that Le Corbusier intended to serve the organised working class. However, due to the size and cost of the project, it began as a government-financed model. Numerous financial problems thwarted the co-operative model.

The lack of building materials in post war France, the additional rounds of financing needed and the seven-year political struggle between a bomb-scarred city and a tired state shackled the initial vision. Utopias don’t come easy.

Fortunately, the second L’Unité D’Habitation (321 apartments) at Nantes-Rezé learned from the morass of the Marseille prototype and was built in two years.

Writing about the five different L’Unité models, Jacques Sbriglio extracted this from the founding documents of L’Unité at Nantes-Rezé: “We are not dealing here with an experimental state project, but with a direct commission from the future occupants of the building, who form the cooperative ‘La Maison Familiale’ in Nantes. The (co-op) members are the labourers and foreman, the majority of whom work at the port. The cost is strictly controlled by the law governing subsidised housing.”

Le Corbusier considered this commission from the militant co-op users of L’Unité Nantes-Rezé as a mandate of the model.

For “La Maison Familiale” (a co-op housing developer) set up in Nantes in 1911, the “driving force was to showcase new town planning concepts as well as vanguard ideas in terms of social housing and architecture”.

Yet the architectural features of L’Unité were to revolutionise modern architecture and stir debates that continue to this day.

Lacking access to steel because of the war, Le Corbusier turned to new uses of reinforced concrete to erect his massive 18-storey single building. The single L’Unité building was almost 150 yards long.

Le Corbusier employed concrete pilotis (pillars) to lift the buildings 26 feet off the ground to provide an open pedestrian horizon. Walking under the building you are not aware of its mass but you are aware of trees, lawns and the surrounding landscape.

Le Corbusier saw each of his L’Unités as vertical villages of about 1,500 people and tried to meet as many of their social needs as possible within the building and grounds. With its acres of surroundings, it was also his model of the Green City.

He thought of the long interior corridors as indoor streets and within the Marseille block there is a shopping street at mid-level that provides a café, a 21 bedroom hotel, retail market and bookstore. In its early years, the retail market was a consumer co-operative.

Le Corbusier designed 23 different apartment types within the building – some that internally were on two floors – and gave all of them balconies and light.

The crowning architectural glory for many is the turning of the rooftop in L’Unité, Marseille, into a collective outdoor space. With the Mediterranean on one side and the Alps on the other, the views from the roof are sensational. However, the uses of the roof have changed over time. In the past, there has been a nursery and a gymnasium; now there is an art gallery and exhibition space.

Tens of thousands of people a year visit each of the L’Unités. They learn a lot about the architect and architecture but too little about the vision it offered for co-operative living. The Unesco Award is a reminder to take a renewed look at the co-op housing legacy left by Le Corbusier.

An architect with a vision to reshape the modern world

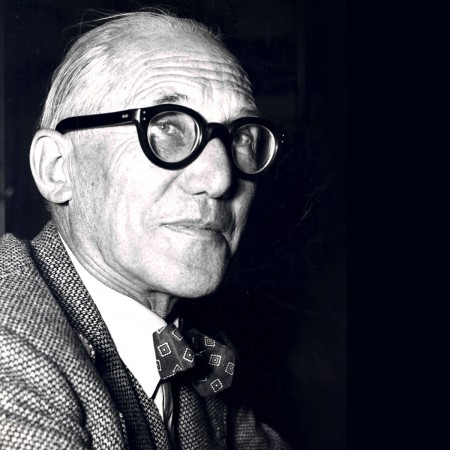

Swiss-French artist and architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris (1887 – 1965, left) was one of the leading pioneers of modern architecture, creating buildings in France, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Russia, Japan, India, the USA, Chile, Brazil and Argentina.

Working under the name Le Corbusier, he used the techniques of the industrial age in his efforts to create a better quality of life in crowded modern cities.

In the 1920s he developed his five points of architecture: buildings lifted on the ground on pilotis, or reinforced concrete stilts; a free façade on non-supporting walls; an open floor plan; long strips of ribbon windows; and roof gardens to compensate for the green area consumed by the building.

Other recurring motifs included a sculpted “Open Hand”, a symbol of peace.

He had ambitious plans for entire cities of steel and glass skyscrapers set in green spaces, and postwar projects like L’Unité d’Habitation were an attempt to realise this on a smaller scale.