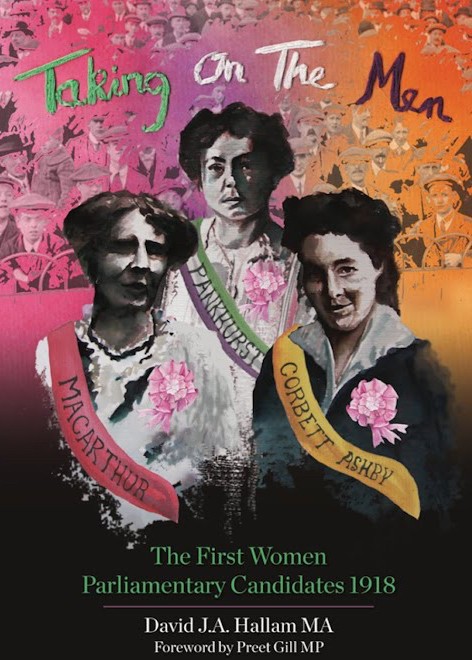

Taking on the Men: The First Women Parliamentary Candidates 1918 by David Hallam (Amazon, £9.95)

Last year, the UK rightly commemorated the historic 1918 General Election, when women were permitted to vote and stand for election for the first time.

The extension of the franchise to women (who met certain qualifying criteria) was a milestone in our nation’s history. But as David Hallam reminds us in this book, the Representation of the People’s Act was the only the beginning of the struggle for women’s representation.

He offers a fascinating and detailed account of the experience of three of the 17 women candidates that stood in the election – all based in his home turf of the West Midlands. In each case the reality of standing for election proved less of a fairy tale than these women might have deserved after the hard-won fight for suffrage. Perhaps most significantly, the challenges they encountered were not unique to this first electoral encounter. They still reflect the experiences of too many women seeking elected office today.

Firstly, the women portrayed here – Christabel Pankhurst, Mary McArthur and Margery Corbett Ashby – all faced the challenge of standing against an established local patriarch in constituencies where they had few or no local ties.

None of the three were the first choice candidate for their party – and they had to contest either with against a sitting MP, enjoying the benefits of local profile, connections and incumbency; or another local establishment figure.

Secondly, it is interesting to note that despite the seismic shift that female enfranchisement the main parties had given little thought to the selection of women candidates, let alone that they might be chosen to fight winnable seats.

Mr Hallam quotes prime minister David Lloyd George as saying: “I am not sure we have any women candidates and I think it highly desirable that we should.” But these women were learning an early lesson – that when it comes to women’s representation it is not sufficient for those in powerful positions to will the ends; they must also will the means.

And it would take until the mid-1990s for a political party to really will the means to transform womens’ representation in Parliament, when the Labour Party elected more than 100 women MPs, many as a result of selection by all-women shortlists.

Thirdly, the women faced the familiar struggles of juggling political campaigning and childcare responsibilities. Corbett Ashby called in support from her mother and father to help care for her young son Michael – something that will be familiar to many parents of political candidates today. In addition, McArthur was criticised for involving her child in her campaigning activities.

Related: Co-op women celebrate IWD 2019

I wonder what they would have reacted if they gad known that 100 years, that same Parliament would still be grappling with concepts as basic as proxy voting for MPs on maternity leave.

Of the many interesting insights in the book, I was struck by the approach of the candidates to the job of appealing to the newly enfranchised women voters. McArthur was most explicit in setting out what might be described as a ‘pitch’ to women saying “If I am returned to the House of Commons, I shall try to voice in a special sense the aspirations of the women workers of this land, to whose cause I have been privileged to devote my life… I shall also feel entitled to speak for the woman whose work never ends – the woman in the home…”

In contrast, Christabel Pankhurst is said to have dedicated much of her campaign to the ‘German Question’ and issues of post-war patriotism. In Birmingham Ladywood, it was Margery Corbett Ashby’s opponent, future prime minister Neville Chamberlain, who felt compelled to hold meetings specifically targeted at women voters and published a leaflet entitled A Word to the Ladies.

It seems none of the three women candidates under discussion sought to address the very real consumer issues of the time – and yet these involved questions such as the availability of food, which would have been a concern for both male and female voters.

This was instead left to the fledgling Co-operative Party, formed just a year earlier; this historic election is notable for another reason; the election of its first MP, Alfred Waterson for Kettering.