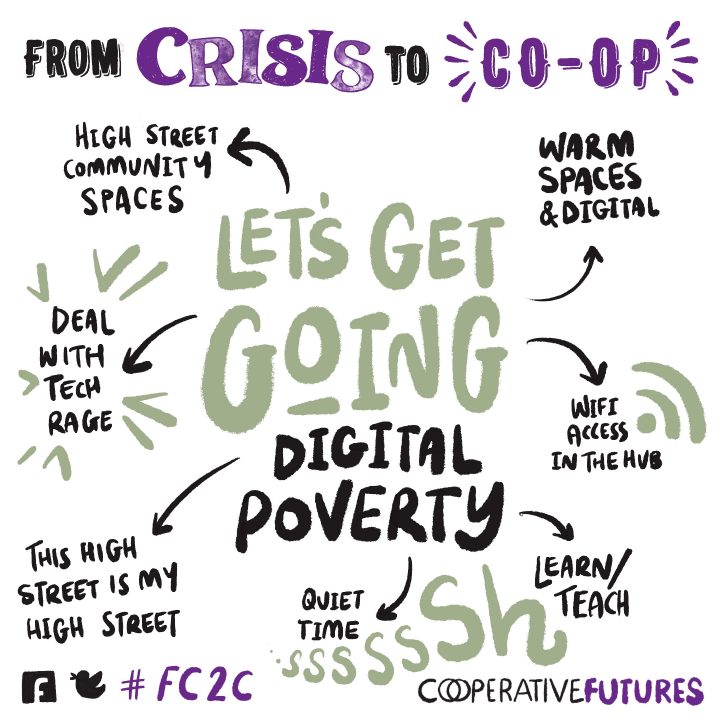

“The best way to demonstrate that co-operatives are effective is to see them in action,” said Jo White, opening the 2023 Future Co-ops conference: From Crisis to Co-op.

Organised in Oxford by co-op development agency Co-operative Futures, the event looked at how co-ops and communities can address the lack of access to basic needs – including housing, food, energy, secure employment and digital access – in a fair, equitable, dignified and culturally appropriate way.

Elizabeth Anderson from the Digital Poverty Alliance (DPA) painted a stark picture. Over 10 million people lack foundational digital skills – with 2 million over-75s digitally excluded, and 35% of young people reporting that they cannot do everything they need to online because of limits to their family’s data allowance. Around 6% of UK households have no internet access.

“Being online or offline isn’t a distinction we can make,” said Anderson, highlighting how without internet access, a child may not be able to do homework that has been set online, some people will be excluded from booking GP appointments, or a family may not be able to search for cheaper electricity tariffs.

DPA is advocating for change by bringing communities together and running projects for potentially excluded groups, including families, teachers and prison-leavers, building the business case for why it is so important to get online.

“The rush to digital is leaving people behind,” said Anderson. “The co-op movement must seize this chance to invest in community locations with devices, connectivity, skills and support.”

Devices, skills and data don’t work without each other, warned Kat Dixon, a digital inclusion advocate and fellow at the Data Poverty Lab. “The internet isn’t a thing, it’s a means to an end,” she said, giving examples of effective digital inclusion projects, from Chipping Barnet food bank providing six months of free data via sim cards provided by the National Data Bank, to a volunteers in Lancashire who dug cable lines and set up their own service provider (B4rn).

“The idea of spaces for digital access is also interesting,” she said. “People need physical spaces to learn skills – similar to the original co-op reading rooms above co-op shops – but also private spaces to live their intimate lives online.”

The conference also heard from Claude Hendrickson who in 2020 became the only black male accredited community-led housing advisor in the UK. “People need a roof,” he said, adding that “the anguish communities are feeling now makes me feel like we’re back in the 70s: strikes, the lack of food, dereliction, communities with no hope or aspiration.”

Hendrickson was project manager on the Frontline community self-build scheme in Leeds which in 1996 saw 12 unemployed Afro Caribbean men and their families build new homes for themselves. He is now calling for co-ops to help solve the housing crisis through community-led housing – and stressed the importance of self-help. “Co-housing, community land trusts, self-builds, custom-builds – these are all a form of co-operation,” he said. “No matter what we do to make a change, when people come together in the community, that’s a co-operative.”

John Reacher from Fuel Poverty Action (FPA) described his organisation’s campaign against the forced installation of prepayment meters. It is now advocating for the implementation of a universal free band of energy, based on need, and has organised a series of direct actions, including vigils and ‘warm ups’, where people occupy public spaces – such as banks and shopping centres – to get warm.

“We want energy supported as a universal right,” he said. “All these crises are interlinked. The millennial generation is predicated by precarity. We can’t save for the future or put down roots – that’s standard for anyone born in the 80s upwards. Poverty makes people invisible; the effect of poverty is that you have to hunker down. The worse the poverty, the less you hear about it.”

Related: Future Co-ops 2019: Can co-operative deserts bloom?

This was a common theme: the acknowledgement that crises around food, energy and housing are an intrinsically linked everyday reality, and often share overlapping solutions. That it’s a situation of poverty that cuts across sectors, regions and demographics.

One place where this is abundantly clear is South Kilburn, in north west London. One of the most ethnically diverse areas in the country, with 400 languages spoken, it has multiple indices of deprivation. Deirdre Woods, a co-founder of Granville Community Kitchen (GCK), spoke about how the organisation was set up 30 years ago by residents to address the entrenched deprivation in the area.

“We looked at all aspects of what a neighbourhood needs to be resilient,” said Woods, explaining that GCK is part of a larger multi-stakeholder co-operative, alongside a housing co-op, a mutual support fund and an educational charity.

“There is no such thing as food poverty; there is poverty, and people are hungry. We are not in a food crisis; we are in a crisis of inequity and inequality. But [the Kilburn community] started with food as most people are impacted by household food insecurity. And they have food insecurity because they are cash poor because income levels are insufficient. The government is violating our right to food right now.”

England as a country is also food insecure, added Woods, who is policy co-ordinator for the Land Workers Alliance. “We import half our food. There are not enough farmers or people entering farming, so GCK is also training people from an agro-ecological point of view. It’s a whole system, about people, culture, care and reducing waste.”

GCK started with free or low-cost meals, particularly to women, children, families and disabled people, and runs a community garden and the Good Food Box – a radical weekly veg bag scheme which charges a range of prices based on ability to pay and is linked to Healthy Start vouchers. They also include veg appropriate to different cultures: “No one else is providing foods that our communities want to eat”.

During the pandemic, GCK began a food aid scheme, but at one point this was serving over 1,200 people a week, which was not sustainable. “Charity can’t feed people, you need solidarity,” said Woods. “We now do a small scheme for people who can’t access public funds.”

She challenged the co-op movement to slow down and not rush into unconsidered responses. “Co-operatives should move away from charitable food aid to co-create solutions with communities,” she said. “And particularly around food that is affordable, nutritious and culturally appropriate.”

Throughout the event, delegates also looked at the challenges in different sectors, extrapolating practical next steps – mapping available support, raising awareness of co-operative answers, finding ambassadors, building capacity and raising new forms of capital. There was also the acknowledgement of the crossover of solutions: digital skills hubs could be linked with community hubs and places providing warm spaces; gatekeeping behaviours need to be challenged; and there was a call to support the movements and federations already active – including Energy4All, Workers.coop, Solid Fund and the Union-Co-ops movement.

There were specifics, too. In housing, there was a call for centralised solutions to encourage existing owners of property or land to sell to the co-op movement – potentially through a renting model. The worker co-op movement called for an international worker co-op meet-up and a rapid response unit to find opportunities within businesses being sold or in trouble.

“Burnout is real, though,” said Nick Greenhill, director of Co-op Web. “People who work in co-ops want to give as much as they can. Sometimes that ends up being too much.”

But as Kat Dixon added, co-ops also have the capacity to “bring joy to a difficult struggle”.

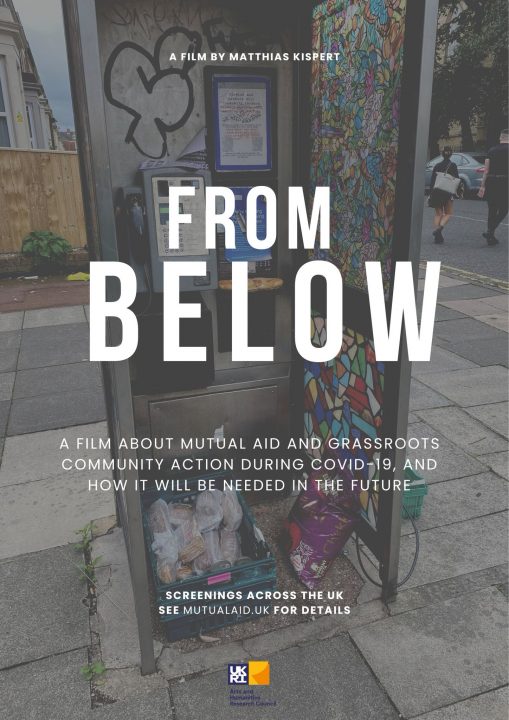

Screening of From Below

Ahead of the main conference, Future Coops hosted a public screening of From Below, a documentary showcasing mutual aid and grassroots community action during the pandemic.

In a Q&A that followed, Dr Oli Mould, a geographer at Royal Holloway, University of London and producer and lead researcher on the project, said the term mutual aid was popularised by anarchist philosopher Peter Kropotkin, who argued that co-operation, not competition, was the driving mechanism behind evolution.

“Pre-pandemic, mutual aid was seen as anti-capitalist, with a distinct role of over-throwing systems,” said Mould. “But during Covid, there was a softening of that political edge.”

In the USA, the term retains a radical anti-racist, anti-capitalist edge, he added. But in the UK, it now has three distinct narratives: mutual aid as charitable, contributory (such as Alcoholics Anonymous) or radical.

Also speaking was Nigel Carter from Oxford Communuity Action (OCA), a black multi-ethnic mutual aid organisation formed in 2019 on the back of community participatory research into men’s health. This research, by Healthwatch Oxfordshire, found that the disparity of life expectancy for men in north Oxford and the south and east areas of the city was 15 years.

“The report anticipated some of the issues that came out of the pandemic, including how it disproportionately impacted the BME communities, many of whom were frontline workers,” he said. “There is a link to stigma here too,” he added, “and links to dignity and the right to food.”

The OCA is “less food redistribution centre, more cultural hub,” he said, adding that the organisation has maintained a genuine sense of mutual aid “by focusing on people acting in solidarity to meet specific local needs”.

“Without this focus, there is a danger that activity can be co-opted by bigger organisations, diverted to a different direction or the values can be diluted,” he warned. “You also need to be cognisant of what tradition you’re from and the traditions you’re in.”

He gave the example of the Black Lives Matter movement, and reminded delegates that this is the 75th anniversary of Windrush. “They brought solidarity economics and the values of mutual aid from the Caribbean,” he said. “They brought Susu, or partner systems [type of informal savings club arrangement between a small group of people] and local credit unions.”

He added: What is important from grassroots organising is to come back to the values of people and collective, but you also need a steady flow of people with ideas and passion.”