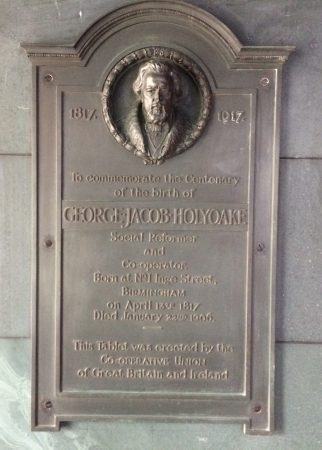

A short walk from Birmingham’s New Street Station, inside Birmingham Hippodrome, is a plaque commemorating the birthplace of one of the most important co-operators of all time. This was the location of no. 1 Inge Street, where George Jacob Holyoake – one of the most influential citizens in the illustrious pantheon of Brummies – was born on 13 April 1817. A radical democrat, freethinker, campaigner for education, founder of secularism, historian and champion of co-operatives and co-operation, Holyoake had a long and eventful life.

From the age of eight he worked with his father at the Eagle Foundry as a whitesmith. He studied and became a teacher at the Mechanics Institute and his political education continued through his membership of the Birmingham Reform League which he joined in 1831. During his lifetime he formed or was on the executive of twenty two different organisations. He was friendly with other leading thinkers including John Stuart Mill. He lobbied Gladstone against tax on knowledge (such as books and newspapers) and for the secret ballot.

From the age of eight he worked with his father at the Eagle Foundry as a whitesmith. He studied and became a teacher at the Mechanics Institute and his political education continued through his membership of the Birmingham Reform League which he joined in 1831. During his lifetime he formed or was on the executive of twenty two different organisations. He was friendly with other leading thinkers including John Stuart Mill. He lobbied Gladstone against tax on knowledge (such as books and newspapers) and for the secret ballot.

He is probably most famous today for defending himself in the last trial for blasphemy in a public lecture. His nine hour oration cost him six months in prison!

He coined the term self-help, later taken up by Samuel Smiles. His legendary book published in 1857 ‘Self-Help by the People: The History of the Rochdale Pioneers’ went into ten editions and was translated into dozens of languages and, it is claimed, led to the formation of 250 co-operative societies within two years of its publication. He also chronicled the history of many individual co-operative societies and to produce the seminal history of the movement as a whole.

His death was marked with a permanent memorial when 794 co-operative societies contributed to the building of Holyoake House in Manchester in his name – which is now home to Co-operative News, the Co-operative College, Co-operatives UK, Abcul and some offices of the Phone Co-op.

James Ramsey McDonald wrote the entry on Holyoake in the Dictionary of National biography. And for the 150th anniversary the BBC commissioned a play for today about Holyoake’s trial and imprisonment, written by John Osborne. Holyoake was played by the most famous actor of the time, Richard Burton, and Mrs Holyoake was played by the equally famous Rachel Roberts.

So how should we remember Holyoake today? The most important lesson we can take from him is his radical commitment to democracy. He spent a lot of time thinking about how co-operators and others could work together. He stated that associationism (one of the many terms he brought into popular use) was an art to be learned. “The moral art of association” was, he said, the art of making co-operative behaviour more likely. That development of a co-operative culture is reflected in his anecdotal style of writing, “folly is a contagious disease”, he said, “but there is difficulty in catching wisdom”.

Lastly he championed collective action and individual freedom. In his autobiographical work, Scenes from an Agitator’s Life published in 1892, he wrote: “The ambition of distinction is wholesome as long as it permits equal opportunity. In democracy there is no chieftainship in which others must submit their judgement against their reason. There is no legitimate leadership, save the leadership of ideas, no allegiance save that of conviction, no loyalty save loyalty to principle.”

Spreading the message of co-operation is as important today as it was two hundred years ago. Holyoake said “I have cared for co-operation more than for any other cause”. Today he inspires us to continue to make the case for co-operation as a vehicle for economic, social and political emancipation.