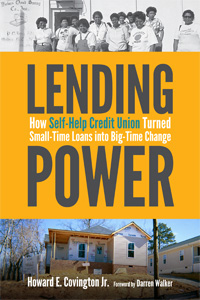

Lending Power: How Self-Help Credit Union turned small-time loans into big-time change, Howard E Covington Jr (foreword by Darren Walker), Duke University Press

Rising inequality and the desire for alternative economic models means co-ops and credit unions are the subject of growing interest – which makes this account of a small-non profit, created to tackle poverty in Reagan’s America, a timely one.

It is the story not just of the rise of a radical credit union but also of its role in the community that shaped it, which saw it work with churches, civil rights activists, maverick philanthropists and city planners to deliver change.

Self-Help Credit Union traces its roots back to North Carolina in 1980, with the formation of the non-profit Center for Community Self Help to lend money to community development projects and worker buy-outs of struggling companies. From these small beginnings – it established its first credit union in 1983 with the $77 proceeds of a bake sale – Self-Help has become the USA’s largest lender to people on low-to-moderate incomes.

In this lively, absorbing look at the organisation, historian Howard E Covington Jr notes: “The credit union’s loan portfolio of 30-year, fixed-rate mortgages to low- and moderate-income borrowers, nearly half of them single mothers and people of colour, proved to be as sound as institutions that made loans to borrowers with established credit.”

Founders Martin Eakes and Bonnie Wright were fired by radical notions and “a belief that the civil rights movement is no over until everyone in society enjoys economic justice”. But there were also conservative values at work: borrowers are expected to pay on time like everyone else, with no giveaways – and “Self Help uses the same financial tools perfected… on Wall Street to benefit poor people”.

Eakes is the key figure in the book, a tough, tenacious individual who survived in his penniless early years by sleeping on his desk and bathing in the local river while hustling for grants to fund projects that would “reconcile socialism and capitalism”. It’s this doggedness that saw him raise the funds for Self-Help to hire its first staff, and helped him weather “a national campaign led by mortgage bankers, payday lenders and the political Right, who were bound to discredit the organisation and, according to Eakes, destroy him personally”.

Against this opposition, Self-Help steadily grew, organising worker-ownership conferences on college campuses, and rescuing and incorporating credit unions in California, Chicago and Florida. Moving to national level, it became a federal credit union in 2008.

Along the way it played crucial roles in vital regeneration projects, such as the redevelopment of a huge, derelict site once formerly owned by the American Tobacco Company in Durham, the North Carolina town where Self-Help was born. When the project stalled in 2003, the credit union worked with local authorities to arrange finance so the regeneration can go ahead. The derelict site is now a thriving hub, providing nearly 4,000 jobs.

It’s a vivid symbol of how credit union principles can make a difference. More evidence of this difference can be seen in Eakes’ battles with regulators and legislators to stop predatory businesses turning non-profits into regular, for-profit corporations. There’s a useful account of Self-Help’s advocacy work, including a campaign to keep health insurer NC Blue as a non-profit; of Eakes’ attack on global banking giant Citigroup over its move into the subprime market; and his work with lawmakers to draft a responsible lending bill.

This fighting spirit was much needed in the poverty-stricken towns of North Carolina, where Eakes once had to frisk workers for guns on their way to a lawsuit against a bankrupt employer for lost pay. He also had to challenge racial bias and a financial industry where an African American business owner would find that “a bank would easily give him a loan for $20,000 Cadillac, but he could not get $100 to buy an acre of dirt to expand his logging operation”.

Lending Power is an object lesson in how the credit union movement can make a difference in such situations. As Eakes said in 2014: “We did not have to be geniuses. We just had to have enough faith in simple things.”

03