The Wiyot Tribe has captured much attention in recent years, with the decades-long process of ancestral land rematriation in Humboldt county, California, leading to the creation of the United States’ first, and so far only, community land trust under tribal law.

In 1860, the Tribe found itself making headlines for a much darker reason: the brutal killing of somewhere between 80 and 250 Wiyot women and children at the hands of a group of white settlers. The massacre took place on Tuluwat island, the spiritual centre of the Wiyot Tribe’s homeland of what is now Humboldt Bay, during its annual World Renewal Ceremony.

Later that year, the island was sold to a farmer and its various uses over the next century led to the contamination and environmental degradation of the land, while the Wiyot’s tribal status was officially ‘terminated’ by the federal government in 1961.

The decades that followed saw the Tribe battle to win back its legal status, organise and raise funds to purchase part of Tuluwat island and clean up the land. More land has since been returned to Wiyot ownership by public and private landowners, and in 2020, Dishgamu Humboldt Community Land Trust was born.

With ‘Dishgamu’ – the Soulatluk word for ‘love’ – the Wiyot Tribe sees “an opportunity for place-based healing that is multi-generational, with benefits that are both immediate and looking ahead to the next 500+ years”.

Dishgamu Humboldt is designed to act as a vehicle for the return of more Wiyot ancestral lands, which, under the Wiyot’s stewardship, can be used for affordable housing, work opportunities and environmental and cultural restoration.

There are around 30 community land trusts (CLTs) in California, accounting for roughly a tenth of the country’s total.

Related: Indigenous co-ops making a difference in Manitoba and Saskatchewan

The California Community Land Trust Network (CCLTN) was established five years ago to bring these CLTs together, to work on statewide policy advocacy that will advance the movement in California. It also facilitates peer-to-peer support and provides workshops and guides for CLTs on key areas such as property tax.

“Every locality has its own challenges, and so each project is responding to the diverse needs of all those geographic locations all over California,” explains Lydia Lopez, the network’s co-director for organising and partnerships.

Although Dishgamu Hulboldt is the only CLT governed under a federally recognised tribe, there is a growing number of Indigenous-led land trusts in California, such as the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy and CCLTN supporter members Sogorea Te’ Land Trust and Tierras Indigenas CLT.

“A lot of people in California are loosely associated and allied with the native movement here, because a lot of the immigrants in California, we are half Mayan or half some other Indigenous group in the Americas,” says Lopez.

“And so there’s naturally an affinity to the Land Back movement, to the rematriation of land and to all the efforts of really recognising the struggles and the challenges that Indigenous people are facing everywhere.”

The first CLT was established in the Deep South by civil rights activists in the late 1960s for Black farmers and their families who had been forced from their homes. It has been noted that early CLT pioneers took inspiration from ancient expressions of communal land ownership globally, and that it is in fact the concept of land as a private commodity that is new.

The Wiyot Tribe says that it chose a CLT model for Dishgamu Humboldt in order to “maintain Wiyot leadership in perpetuity, remove land from the speculative market, and direct its use in ways that build both community and

individual wealth”.

It is this level of collective control that Lopez highlights as a major benefit of CLTs for Indigenous groups, who have historically been forced to leave their land and relocate to various places that were not traditionally their home.

“They have been told what to do, what to wear, what language to speak, and their children have been removed from their homes. There was so much loss of autonomy and a very intentional process of destroying the fabric of that culture and destroying the fabric of those communities,” says Lopez.

As the Wiyot Tribe continues to rebuild itself, its work through Dishgamu Humboldt is also responding to the dual crises of ecological destabilisation and lack of housing which touch the lives of everybody living in the area.

The Wiyot Tribe says that the lack of access to affordable, safe, and healthy housing “not only impacts the ability of Wiyot people to remain in their homeland, but threatens the ability of the entire community to thrive in right relationship to the land”.

“Short-sighted or profit-driven responses to current housing market pressures threaten to destroy natural resources, put communities in the path of environmental hazards, and ignore the needs of historically underserved communities.

“Dishgamu Humboldt seeks to establish radically alternative forms of housing development that remove the profit-motive and empower communities.”

Dishgamu Humboldt CLT is currently responding to this issue with its Jaroujiji Youth Housing Project, a US$14m (£11m) project involving the restoration of three buildings in the city of Eureka to provide 39 beds, including six private studio units, for homeless youths.

When the project funding was secured at the end of last year, tribal administrator Michelle Vassel explained the reasoning behind the project: “Housing prices continue to soar, young people just starting off in life are struggling. Our work and this project are about stabilising housing, and providing care and support so that youth in our community have a healthy safety net and a place to grow, heal and develop.”

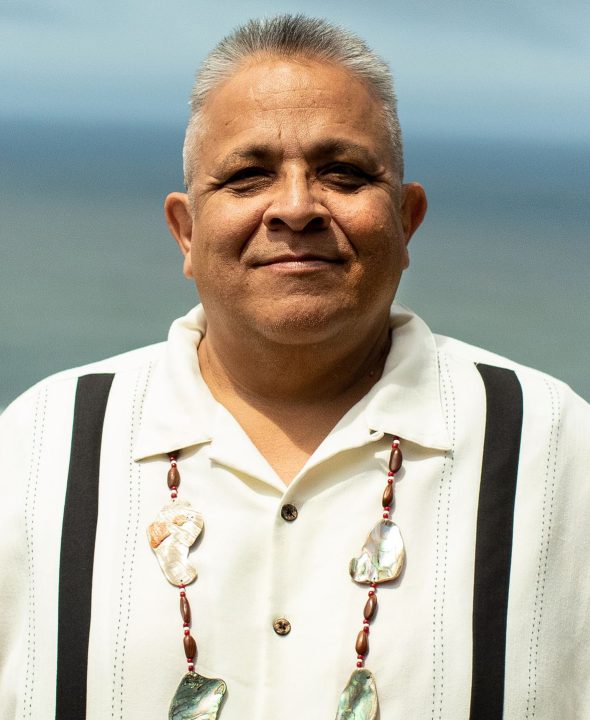

Ted Hernandez, tribal chairman, described the project as “a true blessing”, adding: “It will help to keep Wiyot youth and homeless youth protected from addictions and dangerous environments that might try to attack them from the outside world. It is our responsibility to keep our children safe.”

Dishgamu Humboldt is associated with the California CLT Network, and though its unique legal set-up currently prohibits official membership of the network, this is a technicality the two natural allies are resolving.

“It is very important to listen to Indigenous wisdom,” says Lopez. “There’s a lot of policy issues, and there’s a lot of curriculum questions. We want to be informed with the lens of the Indigenous communities that are part of our network.”

Currently in the midst of board recruitment, the CCLTN is actively trying to incorporate Indigenous voices into its various working groups and at the board level, with the intention of both redressing past historical harms and learning from Indigenous perspectives to create a better future for everyone.

“When I talk to our network members, a lot of them are talking about healing”, says Lopez.

“Access to the land and going back to their ancestral lands is part of the healing process for a lot of Indigenous groups, because we see the land as a place where we can enjoy nature, a place where we can share food and stories with our families, a place where we can rest, and a place that is open to anyone. There’s no exclusion from these places.”