Look inside an average wallet (physical or digital), and you’re likely to find membership cards for various clubs, services and loyalty schemes. Among these, you may find one or more membership cards for a co-operative retail society.

More than eight million retail society memberships are held in the UK, but becoming a member of a co-op means more than joining a loyalty programme – it means ownership. Membership of a local co-op society also represents a deeper belonging to a global co-operative movement with a distinct set of values and principles, whether individual co-op members are aware of this or not.

A key component of UK retail societies since their inception in the 1800s, membership originally meant that for around a £1 share, customers could participate democratically in the business, by having a say in how the business is run, as well as participate economically through receiving a dividend, or share of the profits, in proportion to their purchases. The ‘divi’ could be withdrawn by members or donated to a local cause.

Today’s retail co-op membership remains, in some respects, largely unchanged – many UK retail societies still charge around £1 for membership (if adjusted for inflation, this figure would have risen to roughly £100 by now), and members still participate democratically, through voting at meetings and electing the co-op’s board.

Related: More than a loyalty card: Global inspiration

Economic participation remains a central part of retail co-op membership in the UK. The majority of societies still distribute a share of their profits to both members and local causes through regular dividend payments, though it is up to the society’s board to set the rate of return, and decide whether to recommend making a payment at all, based on the co-op’s financial health in a given year.

The Co-op Group, for example, has not paid a dividend to members since it entered financial difficulties in 2013, and has instead introduced a reward scheme which currently offers members 4p of rewards for every £1 spent on eligible products in its stores, half of which goes to local community causes. Alongside this, retail societies have developed their membership offers beyond voting and dividends to include a range of benefits including in-store discounts, member events and more.

A number of societies have also developed digital membership platforms, such as Midcounties’ Your Co-op members app, which features a virtual card and information on current member deals.

The specific benefits a member receives from their local retail society may be luck of the draw depending on where they live, but what if they find themselves in an area where multiple societies operate? With shared branding across some of the independent retail societies, co-ops’ separate membership systems have the potential to cause confusion at the till.

Related: The co-op cloverleaf – and the issues of shared branding

Over the years, there have been attempts to join up some of these dots, through affinity schemes where co-op member cards can be used in multiple societies’ stores. A few years ago Midcounties, Central, Chelmsford Star, Southern and the Co-operative Group entered into an arrangement whereby members of each society could use their cards at any of the five societies to earn dividends. However, the Group’s move away from dividend payouts towards a rewards scheme over recent years has led to a situation where Group members are able to earn a dividend by shopping in other society stores, but members of the other retailers cannot earn a dividend by shopping in Group stores.

This prompted Southern to exit the arrangement in 2021, citing that it was “no longer reasonable” to accept giving up a proportion of its profits to Co-op Group members without reciprocal benefit to its own members.

A Co-op News reader wrote to us last month to describe a situation where he found himself in a town with three co-op shops, each run by a different society – Group, Southern and Radstock. Choosing the Southern store, he didn’t show his Group card as he knew they had withdrawn from the mutual acceptance of cards, but it prompted him to question why societies aren’t doing more to embody co-operative principle number six – cooperation among co-ops. And it prompted us to do a bit of digging. This table gives an overview of what members receive from different UK retail societies – and which cards can be used where.

Our reader’s assessment of the challenges currently facing UK retail societies is that in recent times their co-operation “hasn’t been led top-down”, but welcomed what looks like a possible move towards more co-operation between (at least the larger) retail societies.

This ambition has been expressed repeatedly by Co-operative Group CEO Shirine Khoury-Haq, who highlighted the “power of co-operation” at the society’s AGM earlier this year, extolling the success of co-ops overseas who have managed to use this to their great advantage by consolidating buying, distribution, IT, marketing and membership platforms.

“We absolutely have to think differently about how we can be better co-operators by working more closely together,” said Khoury-Haq.

Despite the competitive advantage economies of scale bring, it is harder to see how some of the smaller retail societies would benefit from a more joined up membership scheme, since it could create more resource-draining admin for little reward.

Societies such as Tamworth describe currently favouring a “cost-effective model that doesn’t rely too heavily on high tech solutions”. For example, its membership ledger is purely a ledger recording the share account values, rather than a system which tracks customer purchases for use in marketing campaigns.

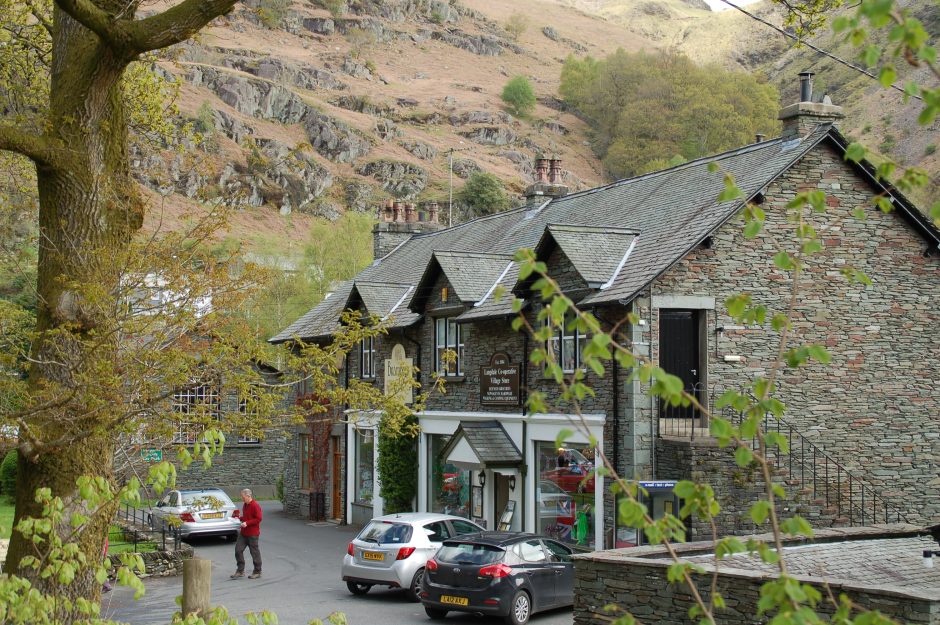

At the same time, some of the smallest remaining independent retail societies are happy to make decisions that make less financial sense on paper in order to meet their members’ needs in the best way for them, such as Langdale Co-operative in Cumbria.

General manager Jeremy Lewis explains why Langdale pays its members a dividend on all purchases, rather than excluding some items such as tobacco or newspapers, which many larger societies do: “We know most of our members personally with just being a small place, and it’s much simpler for us just to pay a members’ dividend on everything.”

Grosmont Cooperative Society, which operates a single village store in Yorkshire, is similarly focused on meeting the needs of its immediate community, which, as the oldest independent co-op in Britain, it has been doing well so far.

“We like having control of what we do”, says society chair Delphine Gale.

“If the fact that we have less buying power is less beneficial, then we draw our benefits in other areas,” she adds, such as being able to respond to a customers’ request for a specific product and sourcing from local suppliers.

On the issue of membership, Gale, like Lewis, paints a picture which looks vastly different to the larger retail societies’ various platforms and apps: “[Members] can come in here at the beginning of December and get their dividends. We hand it to them in an envelope, in cash, and off they go.”

While there might not be a need for every single co-op to share membership benefits or platforms across the board, the argument for at least more conversation and mutual understanding within the retail society family is compelling.

In her Co-op Congress speech, Khoury-Haq went on to pose the question of how co-ops might work together to create a “co-operative ecosystem” capable of challenging competitors while promoting co-operative values. With a retail society landscape as rich and historied as the UK’s, the development of a more co-operative ecosystem is a large yet worthwhile challenge.