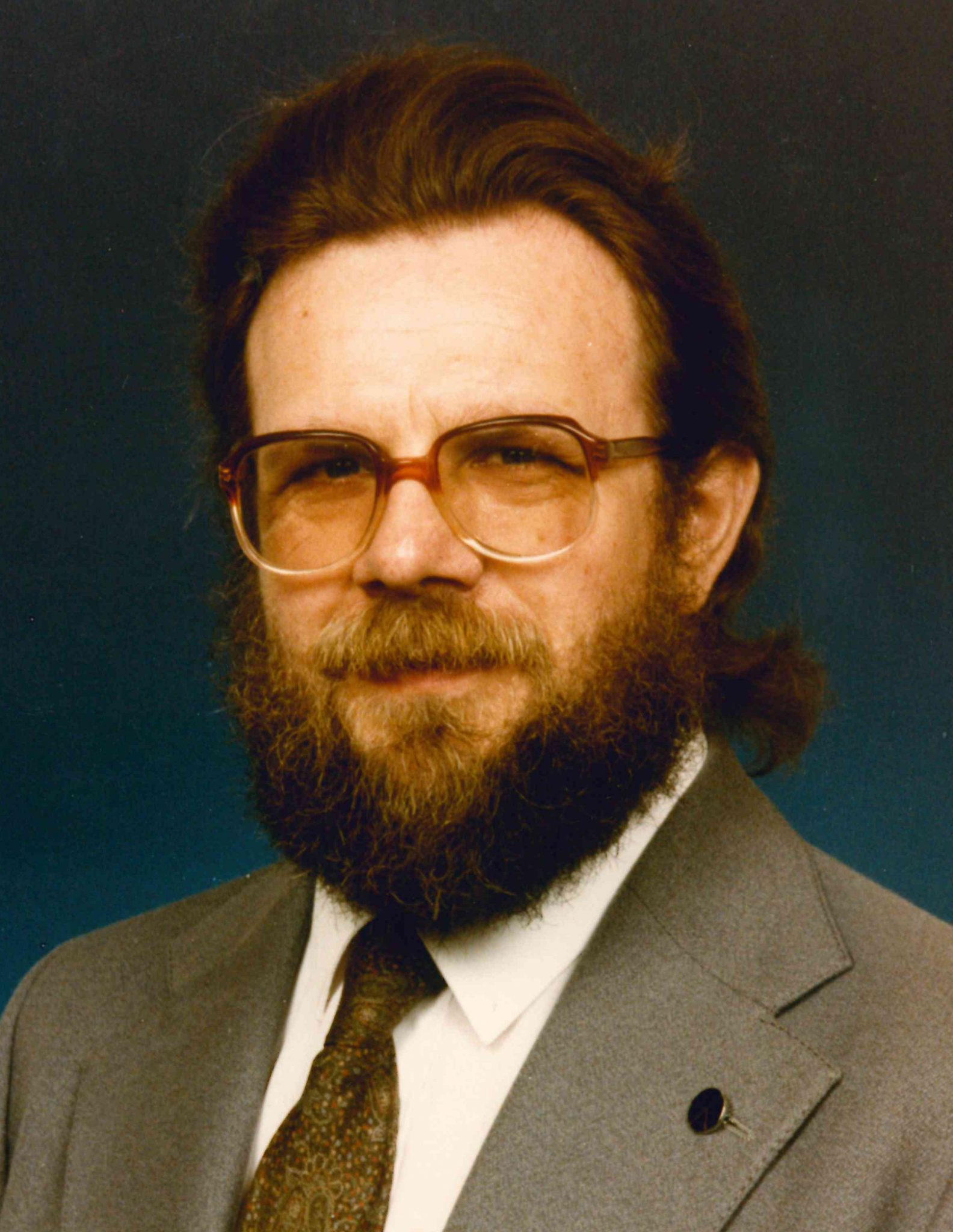

Malcolm Hornsby will be remembered by many co-operators as a passionate and inspirational adult educator who would happily spend breaks sharing his many other enthusiasms, particularly his eclectic musical tastes and his life long love of books – old books in particular.

After a 1960s life with motorbike and guitar and activism in CND, Malcolm returned to education as a mature student. He graduated with a degree in economic history from Sheffield University and undertook VSO in Nigeria, prior to working for the Workers Education Association, interspersed with work in a bookshop in Hay-on-Wye.

Malcolm joined the Co-operative College in the mid 1970s as a lecturer on the policy studies programme for adults without formal qualifications. He readily identified with the challenges his students faced and inspired many to succeed and go on to higher education. An active trade unionist, Malcolm was chair of the College branch of NATFHE for many years.

In the early 1990s he decided it was time to pursue his desire to become a full time bookseller, specialising in antiquarian books. He supplemented this new venture with work as a college associate.

He was a key member of the small team that developed and delivered a committee training programme for the CWS in Scotland following the re-organisation of its democratic structure. The success of this programme led to the College being asked by the new chief executive of the CWS, Graham Melmoth, to develop a training programme for its senior management on Co-operative Values and Principles.

Malcolm helped develop and deliver the programme, initially to the 200+ senior managers through residential workshops, followed by regionally delivered day workshops for over 1,000 managers. The programme proved one of the most successful ever for the College, being customised for delivery to many co-operatives in the UK and internationally.

Stephen Yeo, chair of the Co-operative College Board at that time, said: “Malcolm was a book-collecting, book-selling, book-loving enthusiast, always ready to search in his own full mind, and on his own and the Co-operative College’s shelves, for things which other Co-op enthusiasts wanted, or which he thought they should have.

“Even when he complained about the way the world or the College was going he did so cheerfully, often with a knowing smile on his face. A memorable, remembering co-operator.”

Malcolm Hornsby passed away in January following illness and was interred in a woodland burial site that is also the final resting place for former College colleagues Peter Yeo and Peter Gormley. He is survived by wife Jill and his four children.

Malcolm Hornsby‘s friend and colleague Justin Andersen gave the following tribute as celebrant at his funeral. Excerpts from his tribute follow:

For many years back in the 70s and 80s we worked together at the Co-op College. I couldn’t have wished for a better friend or colleague.

I must be forgiven for saying he was about the most disorganised teacher I have ever come across. His desk would be stacked high with papers, magazines, books and goodness knows what else. I doubt very much whether he had any idea what a lesson plan was. None of that mattered; he was a magically inspirational educator. His exam results were always good, and his students came first. More than once this brought him into conflict with the College authorities.

His principles always came first. He refused to join the College’s Credit Union because he thought it dominated by management. He fought long and hard to persuade Leicester Coop to boycott South African goods.

Never a picture of sartorial elegance, he almost always refused to wear a suit. Except, on one occasion, he turned up at a CND rally in London wearing a very smart suit, perfect overcoat and highly polished shoes. I never quite worked out why.

His depth of knowledge of Labour and Co-operative movement history never failed to amaze me. Prior to the miners’ strike he argued long and hard that they could not come out unless there had been a proper ballot. Day one of the strike, he tells me I must come with him to picket a Leicester colliery. “But Malcolm,” I said, “there has not been a ballot.”

Malcolm’s response? “**** the ballot, they are out and I’m supporting them.”

That’s the Malcolm I knew and will remember with great affection.