Coould co-ops hold the key to the housing crisis? At the Co-operative Congress in Wakefield, delegates heard from community land trusts, co-housing initiatives and student housing co-ops on how to rethink housing.

Home ownership across the UK is at its lowest level in 30 years, while two thirds of adults under the age 30 are unable to afford a home.

Suggesting one solution, Nathan Bower Bir, who is doing a PhD on co-operative housing, talked about the housing projects developed by Students for Co-operation.

“Students have no control of the material aspect of their housing,” said Mr Bower Bir, who lives in the UK’s largest affordable student-run housing project in Edinburgh.

This co-op provides affordable, tenant-run housing to 106 student members, who run it via a consensus decision-making process.

The first student-housing co-op was set up in Birmingham through the support of the Phone Co-op, who purchased the property in mid 2014 to offer on a lease. Another co-op opened in Sheffield in 2015 and a group of students is also exploring setting up a similar co-op in Aberdeen.

The groups is now looking at setting up a federation of student housing co-operatives which would own properties to run as housing co-ops.

Other models are also being explored across the country. Leeds Community Homes, a community benefit society, is working to build and renovate housing, using a community land trust model.

Through a community share offer launched last year, they were able to raise 360,000 and purchase 16 flats in new Climate Innovation District, a new development in city centre of Leeds. Nine of these will be kept for social rental while seven will be sold as affordable units. They expect the first tenants to move in in 2018.

Jonathan Lindh from Leeds Community Homes told Congress his organisation raised its first £100,000 through a community share offer, which was match-funded by the trust Power to Change.

Leeds Community Homes expects to begin paying interest on shares – with 2% interest due to accrue to members’ share accounts from 2020 – and to create 1000 affordable, sustainable homes in Leeds over the next 10 years.

Another panelist, Andy Edwards from Transition by Design, talked about the One Planet Affordable Living (OPAL) Report, which aims to identify successful mechanisms for developing sustainable housing communities.

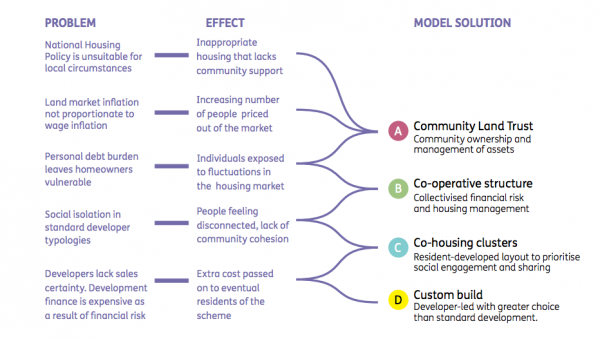

The report, which helps identify five problems and potential solutions, is based on case studies from across Europe as well as interviews with industry experts.

“It’s 20-month research project, reaching out to groups across the country trying to understand what their needs are, what resources would make it easier for them to build up that scheme,” said Mr Edwards. “We try to act as a broker as well between community groups and resources they are trying to access.”

The research found that community land trusts promote community ownership and management of assets via collectivised financial risk and housing management, which helps to address the issue of people being priced out of the market as well as individuals being exposed to fluctuations in the housing market.

Co-operative housing models also enable people to feel more connected through resident-developed layouts to prioritise social engagement and sharing.

Another example came from Terrace 21 a project run by the Northern Alliance Housing Co-operative (NAHC), which was set up to work alongside residents to protect and enhance community ownership of land and properties within the Granby 4 streets area of Liverpool.

NAHC is a member of the Granby 4 Streets Community Land Trust (CLT) – created as a reaction to the Housing Market Renewal initiative, a scheme of demolition, refurbishment and new-building which ran in the UK between 2002 and 2011.

As part of the programme, communities were evicted in an attempt to renew failing housing markets in nine designated areas of the North and Midlands of England, including the Granby streets area. There are 200 houses on the street, 150 of which have been empty since the 1990s. But some those who owned their homes decided to stay and got involved in the local community, running street markets and planting around the empty houses.

“That failure narrative resulted in community resistance,” explained Gemma Jerome from Terrace 21.

The co-op aims to ‘eco retrofit’ five empty properties in the area. The members will live in five two-bedroom terraced houses on Cairns Street, Liverpool 8, creating environmentally sustainable, permanently affordable housing for people on modest incomes. The rental payments will be based on 35% of net household income, making the homes affordable.

Existing members of the Terrace 21 project already either live or work in the Liverpool 8 area. The renovation work started on 11 properties in 2014, after the CLT had gained support from the council for the project. Once completed, the CLT will own five properties for affordable rent and will have sold six at an affordable price to pay towards the renovation works.

Can such projects be rolled over in other areas? Ms Jerome thinks there is a great opportunity for knowledge exchange and making open source resources available for other groups wishing to start up mutual housing ownership schemes.

Nathan Bower Bir argued that for co-operative housing to succeed, the support of the government and other institutions was crucial, but that existing co-ops should take the lead. Responding to a member of the audience who suggested there was not enough money in the co-operative movement to get housing co-ops off the ground at any significant scale, he said: “The movement has the resources. The question is whether the larger co-ops have the will and the smaller co-ops have the joint organisational capacity to provide that financial support. We’re getting closer, but there’s plenty more work to do.”