Neville Chamberlain continues to be remembered for his policy of appeasement in the 1930s. Less well-known is that he is the only British prime minister to have had a species named after him.

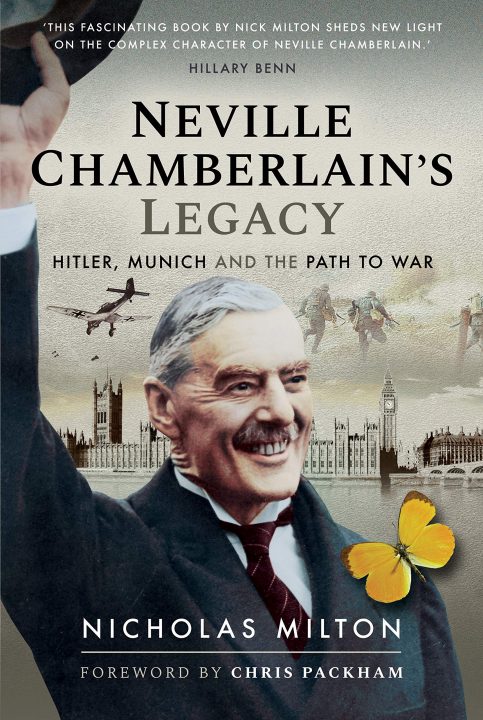

In his book, Nicholas Milton describes how, when running a plantation in Andros, Bahamian islands, Chamberlain captured a new butterfly species, which was named Pyrisitia chamberlaini after him.

A military and natural historian, Milton touches on Chamberlain’s interest in natural history and passion for bird watching and entomology, which helped him cope with the pressures of high office.

Based on letters between Chamberlain and his sister, the author looks at Neville’s reluctance to get involved in politics until the age of 37. He decided to stand for election as a councillor to continue the family’s legacy after his father was unable to continue his political career following a stroke.

Within just five years of entering politics, he became chancellor of the exchequer. His brother Austen, whose career had started much earlier, was named foreign secretary – a role which saw him negotiate the Locarno Pact (1925) and receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

The book also explores the Neville Chamberlain’s legacy beyond appeasement, through his conservation work and track record as minister of health and chancellor of the exchequer. It also looks at the strained relationship between Chamberlain and other Conservative politicians at the time, including Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden, who both disagreed with his policy of appeasement.

Perhaps of most interest to co-operators will be the chapter discussing Chamberlain’s decision to tax co-operative societies while chancellor.

Milton, whose day job is head of communications at the Midcounties Co-operative, is familiar with the co-operative sector. He explains how

co-ops were an ideal way for poor people to save by acquiring their dividends, especially those who did not have bank accounts.

Popular with the working class, co-ops were less liked by small shopkeepers who feared co-ops would take away their trade. Chamberlain’s proposal to tax co-operatives was opposed by the prime minister of the national coalition government, ex-Labour man Ramsay Macdonald, and Samuel Perry, the Co-op Party’s first general secretary, who led a campaign against the move.

Yet, in spite of a petition signed by one million people calling to protect the status quo of co-ops, the legislation was forced through by Chamberlain after an inquiry concluded that the divi was a bonus, not a redistribution of profits and should therefore be taxed.

Through Chamberlain’s direct account of the events from archives and letters, Milton is able to offer a complex portrayal of the man himself, and of a skilled politician who was pursuing peace while at the same time re-arming his country.

Yet letters quoted in the book might also make readers wonder whether the PM’s vanity and belief in his ability to secure peace by winning over Mussolini and appeasing Hitler prevented him from grasping the scale of the coming crisis.