A Useable Past? Volume 1: Victorian Agitator

George Jacob Holyoake: Co-operation as ‘This New Order of Life’

By Stephen Yeo

(Edward Everett Root, Brighton, 2017)

For anyone active in the co-operative movement in the late nineteenth century there would have been one familiar bushy white beard to look out for at conferences and events. The beard (and the person to whom it was attached, George Jacob Holyoake) was a regular feature of the movement’s gatherings. Holyoake was an active delegate at most Co-operative Congresses and, from 1895, at the International Co-operative Alliance conferences as well. He was, by the end of his life, recognised as the G.O.M. of the co-operative world: the Grand Old Man.

We have not necessarily remembered the history of our co-operative pioneers particularly well, but Holyoake has had a little more luck than, say, Edward Vansittart Neale, Lloyd Jones or J.T.W. Mitchell, in that his name was bestowed on the new headquarters building of the Co-operative Union when it was opened in 1911, five years after his death. Holyoake House is now the home of Co-operative News, Co-operatives UK, the Co-operative College and more – and the G.O.M.’s bust still occupies its own niche inside the building.

Keen-eyed co-op detectives will find his name elsewhere, too. When local co-operative societies engaged in house-building (as many did in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries), some chose to name their new streets after co-operative leaders. Holyoake Streets can be found in Manchester, Leicester, Hoddlesdon (Lancs), Wellington (Shropshire), Ferryhill and Todmorden – a memorial of a kind to his life.

But Professor Stephen Yeo has now come up with a rather more valuable tribute to the life and thinking of George Jacob Holyoake. Yeo, one of our most eminent social historians (as well as the recently retired chair of the Co-operative Heritage Trust), says he was spurred on to take another look at Holyoake at a conference during the 2012 UN Year of Co-operatives. And the book he has now produced, A Useable Past?: Victorian Agitator, George Jacob Holyoake, has been written, he says, with the aim of answering the question: could Holyoake’s life and work help co-operative and associated movements to move forward in the modern world? This is, in other words, not intended by Yeo primarily as a scholastic undertaking reviewing the past but rather as an extended essay teasing out ways that Holyoake may be able to help us in today’s difficult political times.

Holyoake is not a straightforward man. Yeo describes him at one point as an ‘idiosyncratic agitator, journalist and moralist’. Holyoake confessed in one of his books to ‘a certain wilfulness of opinion which might perplex and perturb his readers’, and his history of the co-operative movement, which was first published in 1875 and was then extended over the next 30 years, is well-known among historians for, shall we say, his own unique way of approaching historiography. On the other hand, Holyoake’s pen wielded real power. His style of writing was an attractive one: Yeo calls his approach ‘impish’ and certainly the pages of Co-operative News were for years enhanced by the witty, quirky epistles he contributed. We should remember too that one of the main reasons why the Rochdale Pioneers are so well known worldwide is because of the highly successful popular book Holyoake wrote about them, Self Help by the People, first brought out in 1858. The book was widely translated and helped to give the Pioneers iconic status.

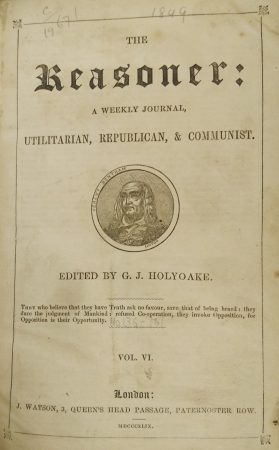

Holyoake is of interest not just to the co-operative world, either. He has a strong claim, if not perhaps for actually inventing the word ‘secular’, of at least popularising its modern usage, particularly through the magazine The Reasoner which he edited for many years. Biographies of Holyoake mention the prison sentence he served as a young man for the offence of blasphemy, being punished primarily for a remark he had made at a public meeting about the cost to the country of the Church of England and its clergy.

But as Yeo points out, secularism should not be treated as a synonym for atheism: Holyoake displayed considerable tolerance of those who did have religious beliefs and – despite a blasphemy trial – was not given to a dogmatic anti-clericism. (We do however have to thank Holyoake, and other early secularists, for giving us the right today to affirm rather than take the Oath in court).

Tolerance is in fact a key word in Holyoake’s universe, as Yeo expounds it. Union (not to be confused with uniformity or lack of difference) is another. What Yeo is particularly keen to put under the spotlight is the moral and ethical underpinnings of Holyoake’s life, and indeed of the early co-op movement more generally. “Reading Holyoake I have been struck by the bold, philosophical-moral, rather than short-term, business-history view which co-operators took of their movement in his day,” Yeo writes at one point.

Yeo also highlights the fundamental achievement of the early co-operative movement in creating its own successful democratic associations in the here and now, not waiting for legislative reform from a far-off Parliament or perhaps for the all-at-once day of revolution to arrive.

“Twenty-first century radicals cannot be reminded enough of the ‘great organisation(s) outside Parliament’ which working people bequeathed to them a century ago, and of the ethic or spirit which brought them into being,” writes Yeo. This is what he refers to as the spirit of ‘associationism’, something which in its impulse meant much more than the running of a local co-operative grocery.

“The extraordinary ambition behind the ‘associated efforts’ of relatively small co-ops working within the Rochdale tradition gets increasingly hard for modern consumer co-operators to remember,” Yeo says at another point in his book.

We are, in fact, homing in here on Yeo’s main impulse behind his book on Holyoake. He is looking to Holyoake to help him rediscover the roots of a radical British tradition, “an unfinished associational-socialist alternative to the Marxist revolutionary tradition”, to see if it can be rebuilt today as an alternative to an overly state-centric approach to radical change. Yeo’s title for the book (the first of a series of three which promise to explore ‘a history of Association, Co-operation and Education for an un-Statist Socialism in 19th and 20th century Britain’) is a Useable Past? The question mark is there to suggest that this is an exploration of whether indeed that history is relevant today – although you feel that, as far as Yeo himself is concerned, the question mark is redundant. For him, there is much to take from co-operation, and from Holyoake’s life, which is very much of value today.

Daringly – not only because of Holyoake’s conventional associations with secularism but also because ‘religion’ is not necessarily a term much discussed among radicals today – Yeo ends his book by exploring in more detail whether we can meaningfully speak of a ‘religion of co-operation’, either in Holyoake’s time or (potentially) today and in the future. Yeo here is exploring fascinating ground which he researched very much earlier in his career. ‘Religion’, in Yeo’s work on Holyoake, is I think being defined by him not as any form of deism but rather as a codification of moral values and humanist beliefs. While I am not sure I am personally convinced of the value of talking of a ‘religion of co-operation’ I do understand the issues Yeo is trying to raise in this part of his book. Yeo ponders whether there is a future in ‘a benign, this-worldly ‘religion’, based on traditional co-operative principles.

This is not, therefore, a conventional biography of Holyoake, nor even a systematic overview of the main issues focused on by Holyoake during his very long life. It is rather a book exploring answers to the question Yeo poses almost at the end of the final chapter: Could moral idealism be unearthed once more, as one of the buried assets of the co-operative movement?