Ahmedabad, a city with a population of 7.4m, is renowned for its cotton textiles – an industry which saw it dubbed the Manchester of India.

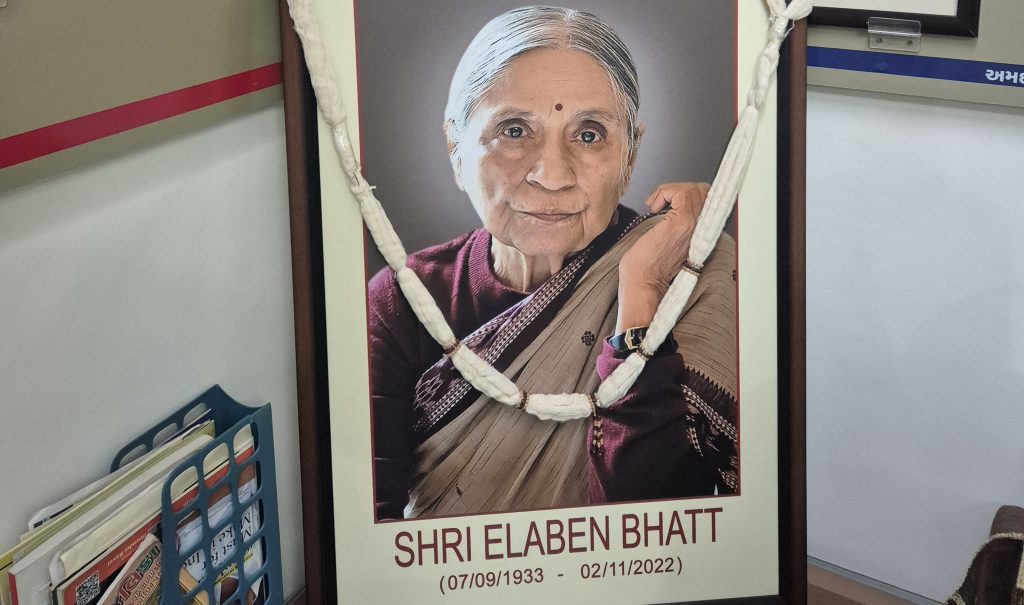

This thriving sector relied on informal women workers, who in 1971 decided to ask for decent wages. They were joined in their plight by the late Ela Bhatt, a lawyer and a labour organiser, who set up the Self-Employed Women’s Association (Sewa) – an association of self-employed informal women workers in 1972.

At first, Sewa focused on getting recognition for these women as workers and securing the same benefits that formal sector workers had. However, after Sewa members negotiated minimum wages and decent working conditions, middlemen stopped offering them contracts, prompting them to set up their own co-ops.

Today, Sewa Cooperative Federation is world renowned, and has inspired similar efforts around the world.

Related: Our coverage of the Global Cooperative Conference in New Delhi

Earlier this month, I joined Dr Sarah Alldred from the Co-operative College on a two-day visit to Sewa. We set off on Monday morning, stopping first at Sewa’s premises. As we waited to be picked up, we were approached by a group of high school students from the local Mahatma Gandhi International School who wanted to know what we were doing in Ahmedabad. Their teacher told us Sewa is well-known in Ahmedabad.

Setting off, our first destination was Sewa’s premises. The journey gave us the opportunity to see the Gates of Ahmedabad, built during different periods of India’s history, starting from 1411 as the entrances to the city.

At the Sewa HQ, we were greeted with a traditional welcome ceremony, being given garlands and having a “tikka” (vermillion) applied on our foreheads.

We got to speak with the chair of Sewa Co-operative Federation, Mirai Chatterjee, its managing director, Jigisha Maheta, and some of their other colleagues.

“Sewa was born when a group of women workers who were street vendors mainly or clothes vendors said – ‘Why don’t we have an organisation for ourselves’,” said Chatterjee.

“At the time it is was groundbreaking event because no such trade union of informal workers existed in India, and that, too, of informal women workers. So when Ela Bhatt went to the trade union Registrar, he couldn’t understand this kind of trade union. ‘Who will you agitate against, who will you fight against?’ And she said – ‘We are from the informal economy. Forty per cent of workers in the informal economy are self-employed. We don’t have an employer but we have many issues. So we would like to organise into a union’ – and that is how Sewa was born in 1972.”

With access to funding posing a crucial barrier for these women, Sewa set up a bank in 1974. It was the first women’s co-op bank – not just in India, but in the world.

Related: Sewa’s journey to empowering informal women workers

“And from a handful of women now we have over half a million depositors,” said Chatterjee.

Sewa Bank offers savings, loans and micro insurance products as part of a full-circle service to help poor women become self-reliant.

We got to visit the bank on our next stop and spoke with managing director Jayshree Vyas, who told us more about the bank’s early days.

She explained that while the women did not know how to run a bank, they said: “We are poor but we are many”. Each of the 4,000 Sewa informal women workers gave 10 rupees to set up the bank.

The bank operates on trust and does not require guarantees. Instead, it relies on community leaders to remind those who fail to pay off their debt. Around 60% of the women taking loans from Sewa Bank are not digitally trained, which means bank employees have to collect in person from the borrowers’ homes. This helps to create a relationship of mutual trust between the bank and the borrower that is not confined to one transaction.

Our journey continued with a visit to the Shri Kada Fruit and Vegetable Cooperative, where we met farmer members. They told us how being part of the co-op means they can pool resources and bypass middlemen. One of the co-op’s leaders runs a collection centre at her house, which enables farmers to drop their produce there and save costs, rather than have to travel to other villages.

The farmers were keen to learn about co-ops in other countries – particularly agri co-ops that are performing well. They also wanted to find out more about the challenges these co-ops face, such as attracting young people – a problem they share.

The second day of the tour began with a visit to a Sewa pharmacy. This particular pharmacy, sited across the road from a hospital, is run by women workers and open to the public. Sewa operates four pharmacies, two of which – including the one we visited – are open 24 hours.

Operating 24-hour pharmacies is not without challenges, with female staff noting that night shifts can occasionally attract angry customers.

Covid posed another challenge, but the pharmacies managed to stay open, offering a vital service to their communities.

Both employees we met have worked at the pharmacy for over two decades. Asked why she had stayed so long, one of them told us that when she started working at the pharmacy, she earned 900 rupees a month. Shortly afterward she received an offer from a competitor for 2,500 rupees a month, which she refused because she felt she was working for a good cause. Now she earns 30,000 rupees a month.

We left the pharmacy and headed towards the Sewa Sangini Childcare Cooperative, a nursery is based in an impoverished area of Ahmedabad. One of Sewa’s 13 childcare centres, it is open to Sewa members – as well as people in the local community, for whom the nursery is an introduction to Sewa; many of them move on to use the federation’s other services.

Children of street vendors are among those cared for. At the centre, they receive three meals a day, lessons, and visits with a doctor every three months. The nursery also engages with parents regularly, including fathers, to ensure they are aware of their responsibilities.

Parents pay only 500 rupees a month for the service – but running the centre costs 30,000 rupees a month, which means Sewa relies on donations to operate it.

At the centre, we met some of Sewa’s insurance agents who told us that explaining the concept of insurance to Sewa workers is challenging. Sewa started its insurance business in 1992 to offer a back-up plan in case members cannot pay loans.

One employee told us that she used to sell sarees – and when she came across a Sewa insurance agent, she realised she could sell insurance products to her clients. She now collects premium payments from 2,900 Sewa members.

Another Sewa Insurance employee told how she grew up in a Sewa childcare centre and now works for the federation’s marketing team.

We left the centre and headed toward Sewa’s production unit for Ayurvedic medicine, one of the beneficiaries of the funding from UK co-ops to Sewa in 2021.

The centre is operated by the Lok Swashthya Cooperative, established in 1990 to provide women in the informal economy with access to basic health services. Today the co-op has over 1,500 members. The medicine produced here is sold in Sewa pharmacies, general practitioner centres and online.

After visiting the centre, we headed back to Sewa’s premises to meet some of the young women participating in its Surjan programme, which was funded by UK co-ops. But how did this support come about?

“There was a quite a severe outbreak of Covid in India,” says Alldred. “The UK co-operative movement wanted to support co-operatives as an act of solidarity and as an act of principle six, co-operation among co-operatives, so we reached out to Sewa Federation and raised £100,000 to send in solidarity.

“Around £70,000 of that fund was for direct support, for oxygen tanks, masks and for working capital to help co-operatives survive through Covid. And then the [remaining] £30,000 was for the two incubator

co-operatives.”

The project focused on providing research and communication skills to young women in Ahmedabad. As part of this, they also received soft skills and self-defence training. The young women we met told us that before taking part in the programme they had never been allowed to leave their homes unaccompanied by male family members. They said the programme had helped them gain confidence. Some were even able to get jobs by using the new skills they had acquired. They were also curious to know whether the UK had any women-only co-ops.

Next, the tour took us to Ela Bhatt’s house. Sewa’s founder died in 2022, leaving a huge legacy. We met her son and sister, both of whom were keen to learn more about Sewa’s current work and the wider co-operative movement.

Our last stop was Mirai Chatterjee’s house, where we were able to delve deeper into the issues of concern to Sewa and its members.

The funding from the UK movement “really touched us deeply,” she said, “because it’s solidarity in action, it’s co-operative to co-operative in action, it is sisterhood in action and we have not been able to forget that.”

This money allowed Sewa to support a dozen small women’s co-operatives across India, said Chatterjee – “two of them savings and credit co-operatives, which almost went under because women couldn’t pay back their loans.

“This money helped to keep the co-operatives afloat during Covid.

“Most of these co-operatives took working capital from us from 300,000 to 500,000 rupees – and the interesting thing is that most of them paid it back. We didn’t take any interest, we had a small margin, just for auditing and other administrative costs, but we thought this was a good practice so some of it was a grant for some of the smaller co-operatives who were struggling.

“But the savings and credit co-operatives, our health co-operative, which produces traditional medicines – all of them returned the money so the fund is still with us and we’re able to lend to others.

“From this experience we have been advocating with our government that, if you want to support women’s co-operatives – small, informal worker co-operatives – through good times and bad, not just during crises, then you need to create this kind of livelihood fund which will provide working capital, either as soft loans or some kind of revolving fund so the co-operatives can grow and prosper.

“The co-operatives have shown their resilience through the whole Covid period, so really, as I said, we are very touched and grateful to the UK co-operative movement.”

We also asked Chatterjee about the challenge of getting young women involved in co-ops, particularly children of second and third generation Sewa members.

She explained that most of them want to do things differently, particularly due to being more educated and understanding digital tools. To appeal to this generation, Sewa used some of the funding from the UK co-op movement to provide digital, communication and research training to young women related to Sewa members.

The next step will be to bring these women together to launch two co-ops – but getting their families’ approval has been difficult.

“As you perhaps are aware, we live in a very patriarchal society and one of the ways that that’s manifesting is control of women and girls’ mobility,” said Chatterjee. “So it’s difficult for girls and women to come out of the home if they are unattended or unsupported by a male family member.

“It has taken a lot of work with the parents to explain that they’re not wandering here and we’re all together as a group, they’re safe and they’re with us, they’re with Sewa and this is a new way of coming together, forming a collective and hopefully a co-operative soon, and getting regular livelihoods in the new way.”

The long flight back to the UK gave us time to consider the key learnings of our visit. While our time with Sewa was short, the UK co-op movement’s support for it is a long-term commitment.

Sewa’s pioneering role in formalising informal women workers was also highlighted in a recent report by the International Labour Organization (ILO).

It says that Sewa demonstrates just how crucial it is that all members – whether professionals or grassroots workers – share the values that the federation represents, and think not just of personal benefits but benefits for the collective and all its members.

Another important lesson is that during the initial period of a co-op relationship, when connections are being made and trust established, physical meetings are irreplaceable, with Sewa staff visiting co-ops and their members regularly.

Covid also showed that while a standalone co-operative will struggle to withstand crises, collective bodies like Sewa Co-operative Federation are able to garner the resources needed overcome them.

The ILO’s report is just one of the many studies highlighting the difference made by Sewa. But while this research speaks volumes, it cannot put into words the sight of happy, well-nourished and looked after children at Sewa’s childcare centres, or of young women empowered to become advocates in their local community.

One thing is certain, with more support, Sewa can not only continue to fulfil its mission, but also keep growing the women’s co-operative movement in India.