At this year’s conference of the UK Society for Co-operative Studies, Nick Matthews, chair of Co-operatives UK and representative on the Co-op Group members’ council, gave a presentation inspired by the Group’s campaign against modern slavery. Its efforts have seen it lobby government and businesses to tackle the rise in forced labour, and devise the Bright Future programme, which offers work opportunities to survivors of the crime. Here, Mr Matthews argues that this anti-slavery ethos is embedded in the co-op movement’s history …

Last year, when the Co-op Group was awarded the Thomson-Reuters Stop Slavery Award for the great work of the Bright Futures programme in supporting former slaves, I wondered what our founders would have thought. Delighted that our values were still intact or horrified that slavery still existed?

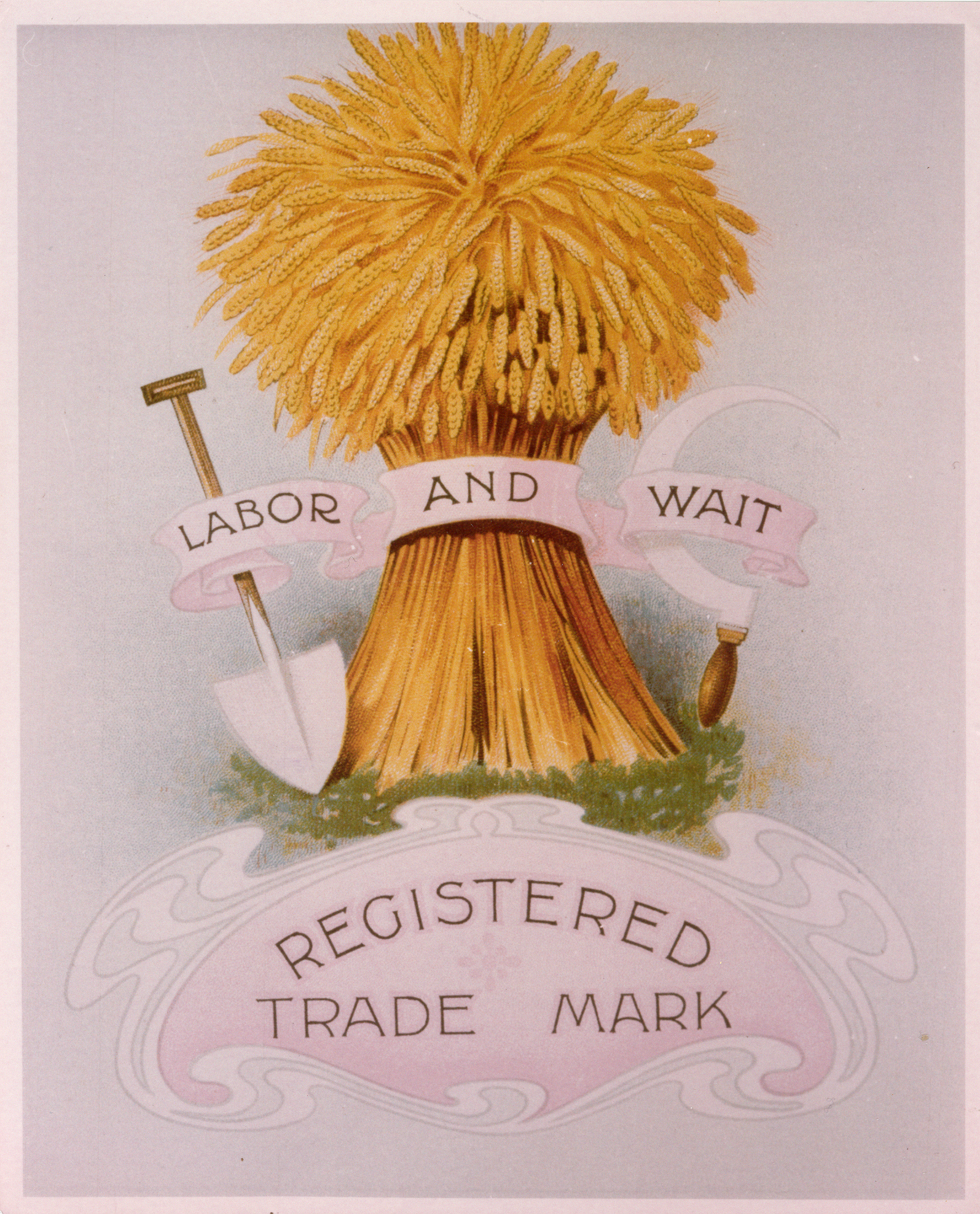

I thought about the early trademark of the Co-operative Wholesale Society, the wheatsheaf with the motto “Labor and Wait”. Labor stood out because it was in the American spelling. It was suggested that this was a demonstration by the founders of the CWS of their commitment to the emancipation movement.

It is generally accepted that ‘labor and wait’ comes from the last line of the Longfellow poem the Psalm of Life.

This raises a series of questions: were the early co-operators supporters of Lincoln and the Union forces? If the phrase was from Longfellow, why was it important and would anyone seeing it understand what it meant?

In short, this is what I have found. Two ideological strands feed the early movement – Chartism and Christian Socialism. Both had a commitment to equality and extending the franchise at home and against slavery.

The backdrop to the whole process of the formation of the CWS was the US Civil War and the blockade of the Southern ports by the Union navy. This prevented the export of cotton to Manchester and Liverpool. Prior to the civil war, there were over half a million operatives in the cotton districts in Lancashire and Yorkshire. By November 1862, over two thirds of them had been laid off. The misery caused has been referred to ever since as the Lancashire Cotton Famine.

Related: More reports from the UKSCS conference

Co-ops were not immune to this economic pressure. There were around 120 co-op societies in the cotton districts. All lost trade and members. Some collapsed. I believe this must have been part of the pressure to form a Wholesale Society.

The Manchester campaign in support of the Union came to a crescendo on New Year’s Eve in 1862 as Lincoln’s proclamation freeing the slaves came into force on New Year’s Day. Two founders of the CWS, John Cooper of Rochdale Co-op and Edward Hoosen of Manchester Co-op, had called the meeting, and some 6,000 people turned up at the Free Trade Hall for the first meeting of what became the Union and Emancipation Society. They went in to be on the founding board of the CWS.

So their anti-slavery credentials are clear. How well did they know Longfellow? Now, it is hard to appreciate just how popular he was. Before effective copyright law, huge quantities of his work were sold. He was the most popular poet in the country, with over 20 British publishers, easily outselling the likes of Wordsworth and Tennyson.

His style of morally uplifting verse fitted the mood of the times. It is astonishing how many of his phrases have entered our language and there is no doubt the founders of the CWS would have been familiar with his work.

So, it seems that it is true that as George Jacob Holyoake wrote, “Co-operative societies had no small share in enabling the people of the two great cotton spinning counties to resist the recognition of a slave dominion.”