The USA’s worker co-ops sector has been experiencing steady growth over the past 20 years. There are now 751 worker co-ops across the US, three times more than a decade ago. Last month, they met in Chicago for their annual conference, an event attended by hundreds of delegates from across the country.

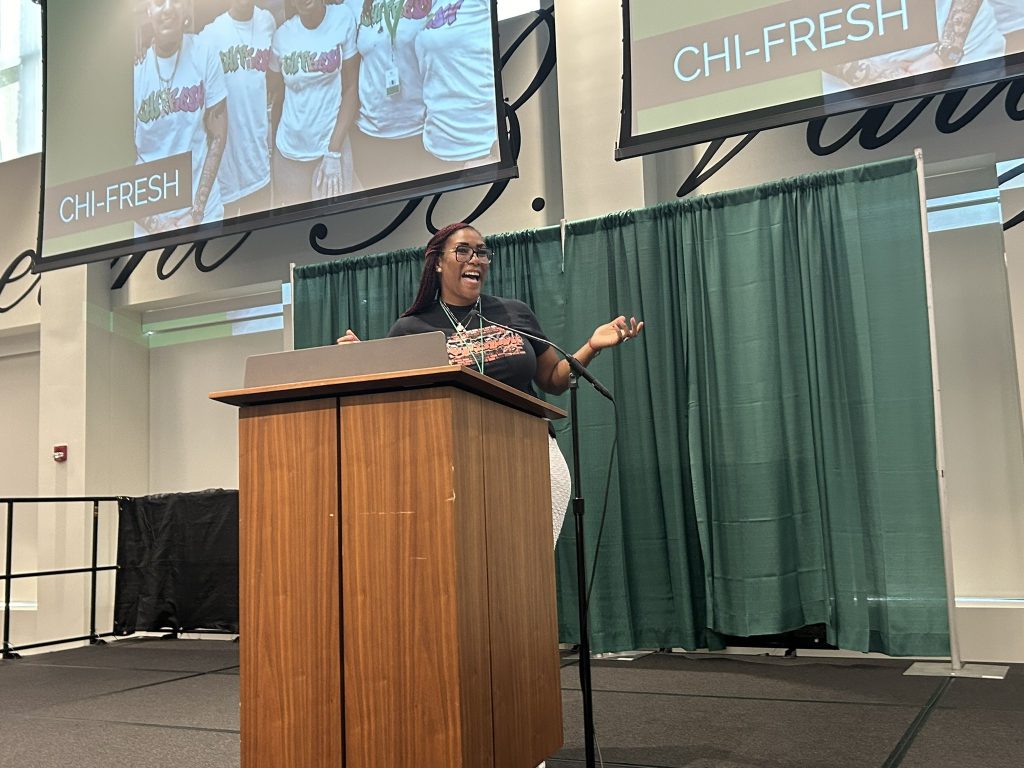

“It takes an ecosystem to build a movement”, Julian Mckinley (pictured above), a co-executive director at the Democracy at Work Institute (DAWI) in the USA told the conference. “We are a movement that is bigger than we’ve ever been before, with more momentum than we’ve ever had before.”

Along with the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives (USFWC), DAWI collects data from worker co-ops, their members and co-op developers to provide insights and offer joint training and technical assistance.

“We equip co-operatives with the tools they need to thrive,” said Vanessa Bransburg, the co-executive director for Operations and Programs at the Institute. She explained that DAWI and USFWC work together to build solidarity, foster collaboration, develop best practices, lobby for beneficial policies and secure funding for co-ops.

The conference was an opportunity to celebrate past achievements and plan for the future.

“It’s our 20th anniversary year so this is a moment to celebrate and reflect and envision what it is that we want to build together, and a moment to expand into a more inclusive network of people and places and institutions,” said Esteban Kelly, the USFWC’s executive director.

“Many of us here have played a role in building the worker co-op sector to where it’s at nowadays, and we’re coming together to steward it into the future and see how we can connect with adjacent movements or economic and social justice movements.”

Kelly thinks community organisers across the US can draw inspiration from the city of Chicago, which granted US$15m (£11.2m) worth of support to community wealth building initiatives, including worker co-ops, limited equity housing co-ops, community investment vehicles and community land trusts, all of which will receive grants and technical assistance.

“That’s an example of the kind of things we’re trying to do and replicate in other parts of the country and the world,” he said.

Over the three days, participants heard from a range of co-operators and community organisers in Chicago, including Kimberley Britt from ChiFresh Kitchen, a food service contractor. Structured as a worker co-operative, ChiFresh Kitchen was set up in 2020 by formerly incarcerated Black women.

“A good job is hard to find after reentry,” explained Britt. “We get a lot of doors slammed in our faces. So we created our own. What’s better than your own business with your own rules and your own wages?”

The co-op’s members are trying to build an ecosystem of co-ops to meet their needs. They are in the process of setting up Jumpstart, a limited equity housing co-operative for people who have been incarcerated and plan to launch a financial co-op to help with their cash flow.

“Where worker co-ops thrive other co-ops tend to thrive too, because they bring that understanding of democratic decision making,” explained Stacey Sutton, an associate professor in the Department of Urban Planning and Policy, and the director of applied research and strategic partnerships at UIC’s Social Justice Initiative.

Other organisations are also helping worker co-ops, including Chicago Community and Workers’ Rights, whose executive director Martin Unzueta told the conference his organisation’s pressure helped to ensure street vendors without a licence get fined rather than jailed.

According to the 2023 Worker Cooperative State of the Sector report produced by USWFC, the growth of the worker co-operative movement is being driven by a significant number of startups, many of these set up by Hispanic and Black communities.

In Chicago they are represented by the Centro de Trabajadores Unidos (United Workers Center) a grassroots member-led community organisation and worker centre set up by a group of volunteers in 2014 to create good employment for immigrant communities.

The centre runs the Southeast Worker Cooperative Incubator through which it supports various co-ops, including Las Visionarias, a Chicago catering co-operative run by immigrant women and New Era Windows Cooperative, a worker-owned co-operative specialising in energy-efficient vinyl windows.

New Era was set up in 2012, after the closure of the Chicago-based Republic Windows and Doors factory. The laid-off workers occupied the factory in an attempt to secure the wages they were owed.

The thought of running the business themselves seemed like a socialist idea at the time, but after watching a documentary about worker takeovers in Argentina, they decided to try it.

Running a co-op can be challenging, warned New Era’s president, Armando Robles, adding that agreeing among workers can be difficult. Despite this, the co-op has continued to grow and is now looking to buy premises and hire truck drivers.

Awareness-raising is crucial to ensuring the co-op business model is seen as a viable option by groups looking to set up new businesses.

Illinois’ Co-op Ed Center (CEC) is trying to address this by focusing on advancing economic and racial justice by educating, training, and developing worker co-operatives in BIPOC communities.

“We should be proud of what we’ve been able to accomplish and continue to accomplish so much more,” said the centre’s executive director and co-founder Xochitl Espinosa.

Time to speak up on policy

The conference also held a session looking at how the USFWC could leverage the movement to improve the ecosystem for worker co-ops, whether by engaging with policy makers, offering technical assistance, or finding financers, lawyers and accountants with the expertise to work with the sector.

Mo Manklang, policy officer at the USFWC, said pressing issues include the new regulatory burdens of the Corporate Transparency Act. “It’s a hard job to help people understand how to keep up the regulations that are going to affect everybody,” she said, adding that the federation is working to ease this by providing a resource centre where worker co-ops can go for information.

But with a revival in recent years of interest in employee ownership, she told delegates it was the ideal time to advocate for worker co-ops. Progress includes the recent national Worker Co-op Development and Support Act, and work at state levels, including in Colorado, Massachusetts, California, Pennsylvania, and many more.

“If you have done any kind of advocacy with your government, at local level, state level, raise your hand right now, all the heroes … We’re going to talk today about why it’s important to do that.”

Lisa Gomez, assistant secretary for the employee benefits, securities administration at the Department of Labor, told delegates she was still on a learning curve when it comes to worker co-ops, “even with the tutoring that I received from Mo and from so many of you across the way … I know that there’s so much for me to learn.”

She urged worker co-ops to tell her department what they need. Its main role, she said, is overseeing the retirement and health benefits offered by businesses to their workers – including employee stock ownership plans (esops). “There is nothing in the law that says, if you want to establish an esop that you have to give a voice to the workers who are contributing … We really thought like, where is that piece of it, and how can people be doing that better?”

One answer the department hit upon was the worker co-op – whose ethos of protecting workers fitted with Gomez’s experience in the union movement. “Whether it’s a co op, whether it’s an esop, if it’s a union, if it’s something that is combined together in some way of those various things, then it’s just a really important and beautiful way to be giving workers the weight and the power that they need,” she said.

To support this, the department set up a division of employee ownership to offer outreach, education and assistance, led by director Becki Marchand. Since then Gomez has been visiting worker-owned businesses of all sizes across the country – such as Coop Cincy, which works to nurture worker co-ops in Cincinnati – to learn more about the sector.

The employee ownership department is now preparing to launch its web page, she added, and is working with the Small Business Administration, the USDA and the White House to push the agenda.

Related: US Department of Labour launches Employee Ownership Initiative

Next up was a panel of speakers sharing their experience of advocacy – who agreed that advocacy is a difficult, time-consuming process that also requires having contacts in government, but is also essential. Policy, said Flequer Vera, co-founder of Co-op Cincy, can affect a co-op’s access to funding, resources and tax credits, and how it is dealt with under labour law. “It’s imperative that we as worker owners get involved in policy,” he said.

Aaliyah Nedd, director of government relations at NCBA Clusa, agreed, adding that it can take a long time to see outcomes bear fruit. Notable successes include the 2018 Main Street Employee Ownership Act.

“There’s still work to be done,” she added, “and these new wins will also take implementation, and will need your voices consistently at the table, engaging with folks, because there’s a saying, ‘if we’re not at the table, we’re on the menu’.”

Hilary Abell, division chief for employee ownership at the Department of Labor, said it was also important to remember that the worker-owned sector is “not just this homogeneous community … You all have different needs, but, and I don’t say this with any disrespect whatsoever, there are parts of the community who are much more vocal, and who are on Capitol Hill telling people what they need.”

She said she is working with policymakers to ensure that all models of worker ownership are considered “so they realise there are different options”.

“Keep knocking on doors,” she told delegates, “and keep writing to people and just keep getting your voices heard, because eventually they do hear.”